Uchovávání zvukové paměti ve střední Evropě: polyfonní píseň Martir Christi

V roce 1477 napsal přední hudební teoretik Johannes Tinctoris, že „neexistuje jediná skladba napsaná dříve než během posledních čtyřiceti let, kterou by vzdělanci označili za hodnou poslechu.“ O tomto výroku, obvykle považovaném za přesvědčivý důkaz toho, že lidé až do devatenáctého století neměli jakékoliv povědomí o hudebních dějinách, se napsalo mnohé. Učebnicové narativy evropských hudebních dějin upřednostňují teleologické a „progresivistické“ líčení hudebního vývoje zakořeněné v estetice devatenáctého a raného dvacátého století – estetice, kterou mnoho z nás, hudebních milovníků a konzumentů, ať již vědomě či nevědomě pravděpodobně sdílí.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]For English version of the article please see below.[/block]

Výzkumný projekt Sound Memories chce studiem jevů, které překračují toto evoluční paradigma, klást danému narativu odpor. Naším jednotícím tématem je pěstování „hudebních minulostí“ v Evropě pozdního středověku a raného novověku prostředky, jakými povědomí o těchto minulostech ovlivňovalo podobu kulturních performancí, a způsoby, jakými byla minulost využívána k politickým a náboženským účelům. Jeden obzvlášť vypovídající příklad je pozdně středověká píseň, která se v 15. a 16. století šířila nejrůznějšími regiony střední Evropy. Tato píseň, obvykle známá pod názvem Martir Christi, se těšila překvapivě dlouhé provozovací tradici, bezpečně překračující Tinctorisovu čtyřicetiletou hranici zmiňovanou výše. Kolace rozmanitých pramenů umožňuje pochopit důvody, proč natolik stará hudba ve zkoušce času obstála, a analyzovat prostředky, jakými byla uchovávána. Tak lze odhalit zcela rozdílné způsoby, jakými lidé k hudební minulosti přistupovali.

Martir Christi

Martir Christi (někdy známá jako Martir felix) je dvouhlasá polyfonní píseň. Její duchovní latinský text naznačuje, že se zpívala při oslavách svatých mučedníků:

Ó, Kristův mučedníku, který byl pro svou počestnost pozdvihnut k nejvyšším poctám a korunován světlem. Nyní jemně rozprostři svůj hlas, písněmi sladce veleb syna Boha Otce, lilii čistoty, který si pro sebe vyvolil svatého mučedníka jako ctihodného služebníka.

Text nezmiňuje žádného konkrétního mučedníka, ať již jménem či odvoláváním se na hagiografické detaily. Tato skutečnost odráží touhu po „liturgické flexibilitě“; tím, že měla takto obecný obsah, mohla se píseň využít v nejrůznějších obřadních kontextech, pokud se v nich tedy pozornost zrovna věnovala nějakému mučedníkovi či mučednici (mužské a ženské skloňování by se pak patřičně upravilo). Za zmínku také stojí, že píseň jako by hovořila sama o sobě, když vyzývá „písněmi sladce veleb syna Boha Otce“. Středověké písně, které tematizují akt zpěvu, nejsou neobvyklé; pravděpodobně napodobují rétorická schémata Písma svatého (vzpomeňme si například na četné hudební zmínky v Žalmech). Zároveň tak mohou vyjadřovat jakýsi druh „korporátního sebeuvědomění“ těch, kteří byli za hudbu odpovědní.

Uchovávání reprodukcí: Martir Christi v utrakvistických rukopisech

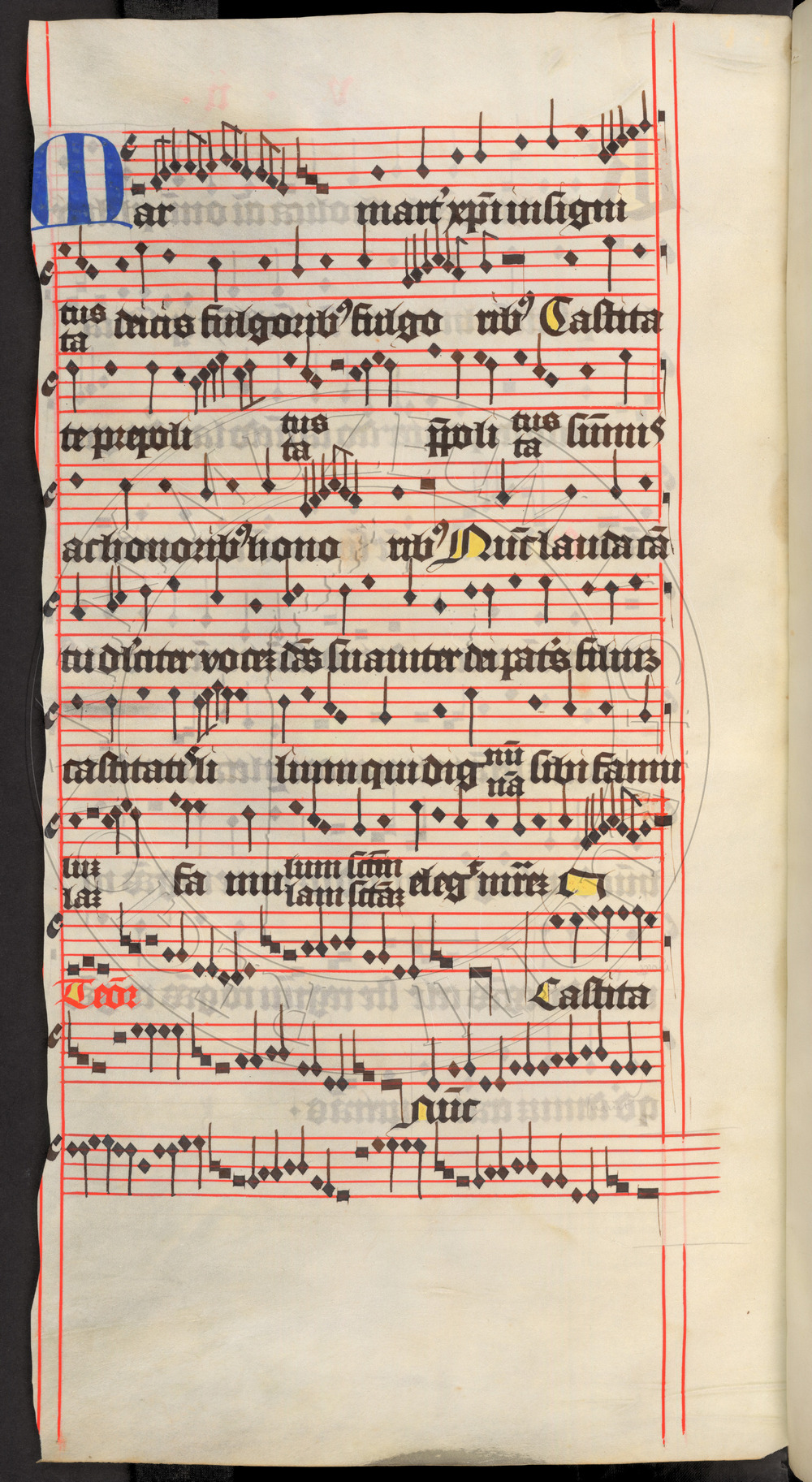

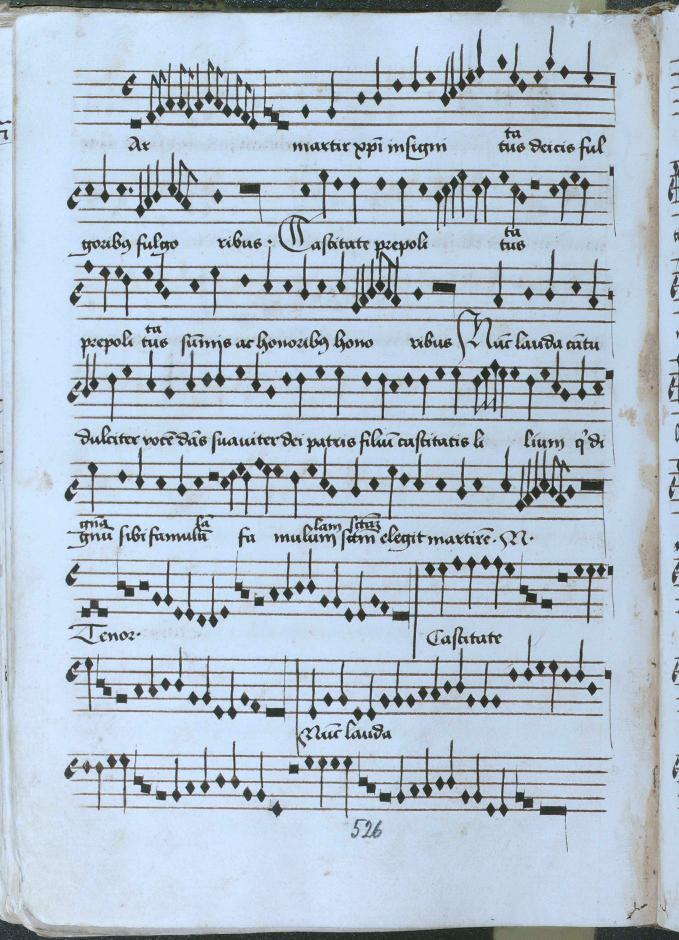

Nejstarší pramen písně představuje Kodex Speciálník, papírový rukopis vytvořený s největší pravděpodobností mezi lety 1485 a 1500 v Praze pro potřeby některé utrakvistické komunity (Obrázek 1). Martir Christi byla zapsána během první fáze vzniku rukopisu zakončené před rokem 1495. Je ovšem nutné si uvědomit, že datum vpisu písně a její kompozice se nemusí nutně shodovat, a mnoho stop naznačuje, že v době, kdy se objevila v Kodexu Speciálník, byla píseň již relativně stará.

Paleografická a stylistická analýza pak skutečně potvrzují, že Martir Christi patří mezi takzvaný „archaický“ repertoár rukopisu. Píseň byla zapsána černou mensurální notací, v níž se všechny notové hodnoty zapisují černě. Tento druh notace byl ve střední Evropě zastaralý již zhruba padesát let. Nicméně písaři z Prahy a zbytku Čech po něm stále sahali v případě tradičního repertoáru utrakvistické církve. Používáním zvláštní, archaické notace písaři symbolizovali starobylost a ctihodnost tohoto repertoáru coby součásti kulturního dědictví své církve.

Ze stylistického hlediska píseň vykazuje některé rysy běžné v takzvaném „archaickém“ repertoáru, jako jsou například paralelní perfektní konsonance či nepřipravené disonance. Ty by v „moderní“ polyfonii složené kolem roku 1500 nebyly tolerovány, ovšem v tomto specifickém repertoáru přežily.

Přestože zmiňované rysy naznačují, že Martir Christi byla v době vepsání do Kodexu Speciálník již relativně stará, její éra rozhodně nepomíjela; píseň můžeme nalézt i v pozdějších rukopisných a tištěných pramenech, což dokazuje, že tvořila součást živé tradice. Je zajímavé se na dva z těchto pozdějších pramenů podívat, neboť jsou příklady toho, jak se ke sdílené hudební minulosti dalo přistupovat rozdílně.

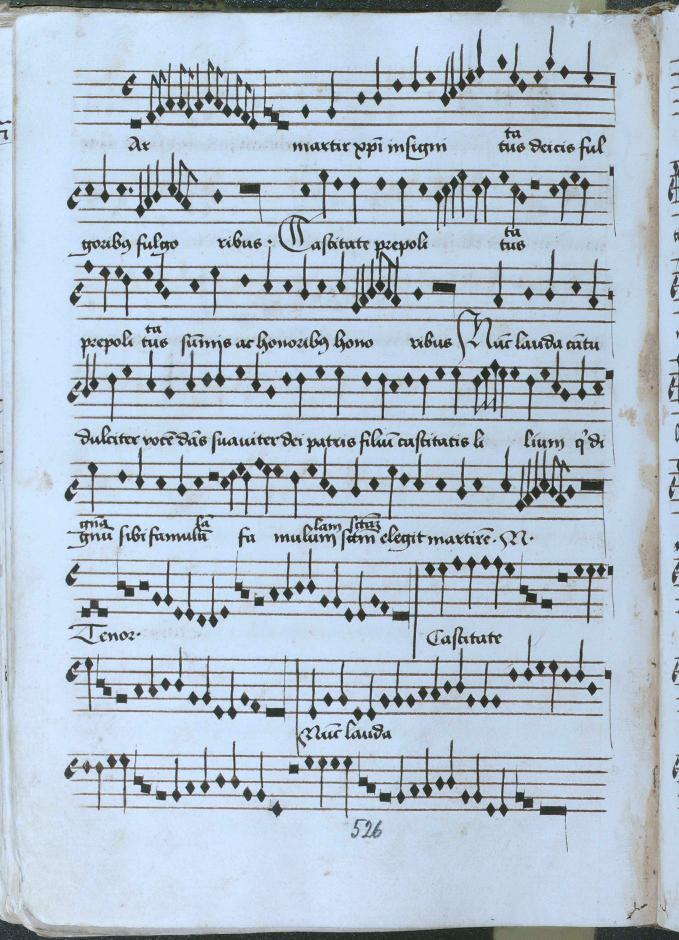

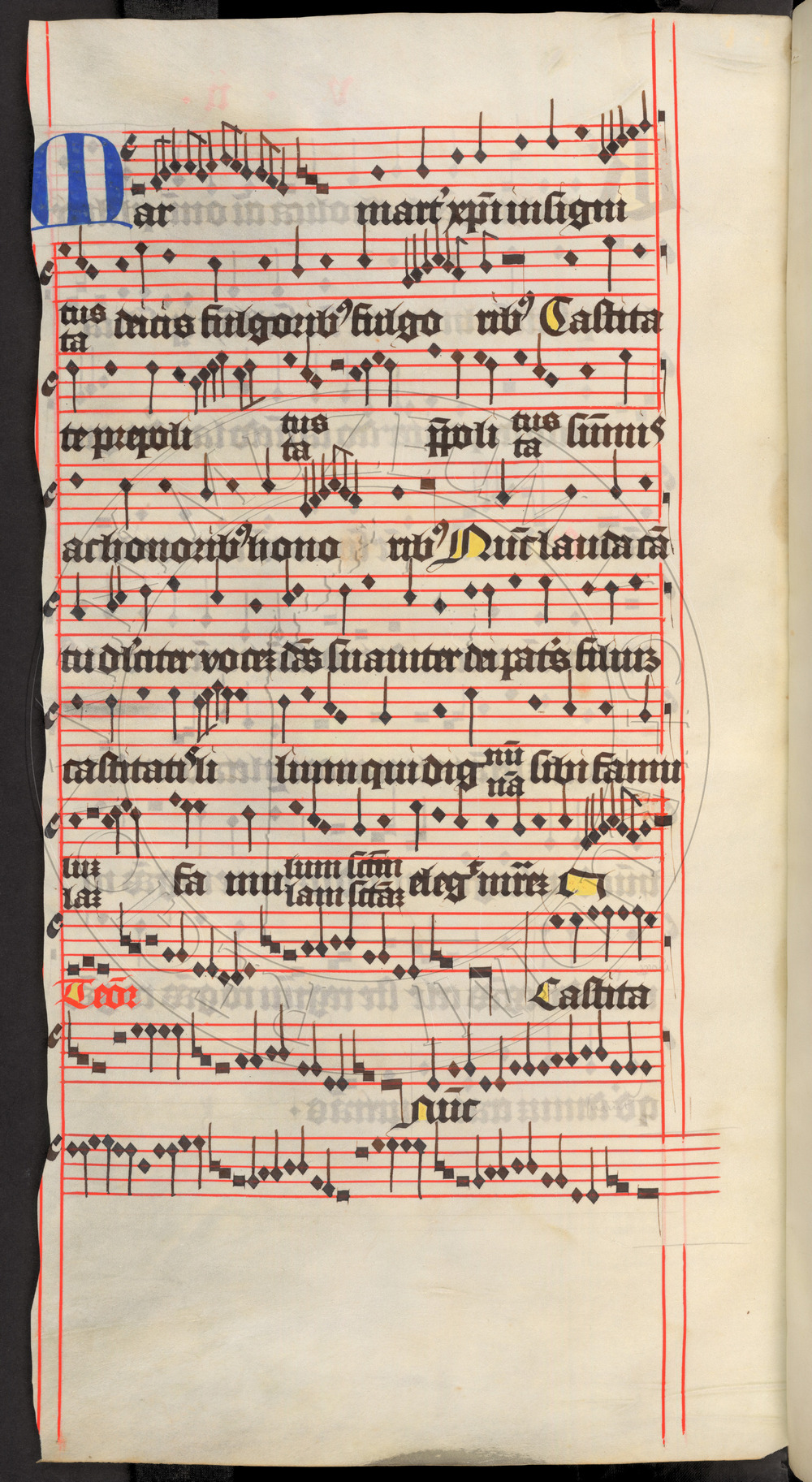

Vezměme si nejprve takzvaný Chrudimský graduál (obrázek 2). Je to utrakvistický rukopis, stejně jako Kodex Speciálník, ovšem vznikl o více než třicet let později, v roce 1530, pravděpodobně pro utrakvistickou komunitu v Chrudimi ve východních Čechách. V době, kdy přenos hudby byl úzce spojen především s procesem opisování, bylo velmi běžné, že písaři zaznamenali i různé varianty a/nebo chyby – ať již skladbu poupravili schválně, nebo se prostě jen přehlédli. Ovšem porovnáme-li píseň Martir Christi, jak je zapsána v Chrudimském graduálu, s její verzí v Kodexu Speciálník, překvapí nás jejich blízká podobnost. Oba prameny píseň zaznamenávají za pomoci stejné, černé mensurální notace. Text je totožný, hudba pak v podstatě také – v obou verzích lze nalézt například i paralelismy a disonance zmiňované výše. Přesnost, s níž se textový i hudební obsah Martir Christi po léta předával, odhaluje touhu po co nejvěrnějším uchování „tradičního repertoáru“. Utrakvistické komunity a jejich písaři přikládali této věrnosti evidentně obrovskou váhu. Po desetiletí či dokonce staletí přepisovali ten druh repertoáru, k jakému Martir Christi náležel, tak, aby zachovali jeho charakteristické rysy bez ohledu na stylistické a notační „revoluce“, které v 15. a 16. století probíhaly. Tento velmi specifický vztah k hudební minulosti bych definoval jako „uchovávání reprodukcí“.

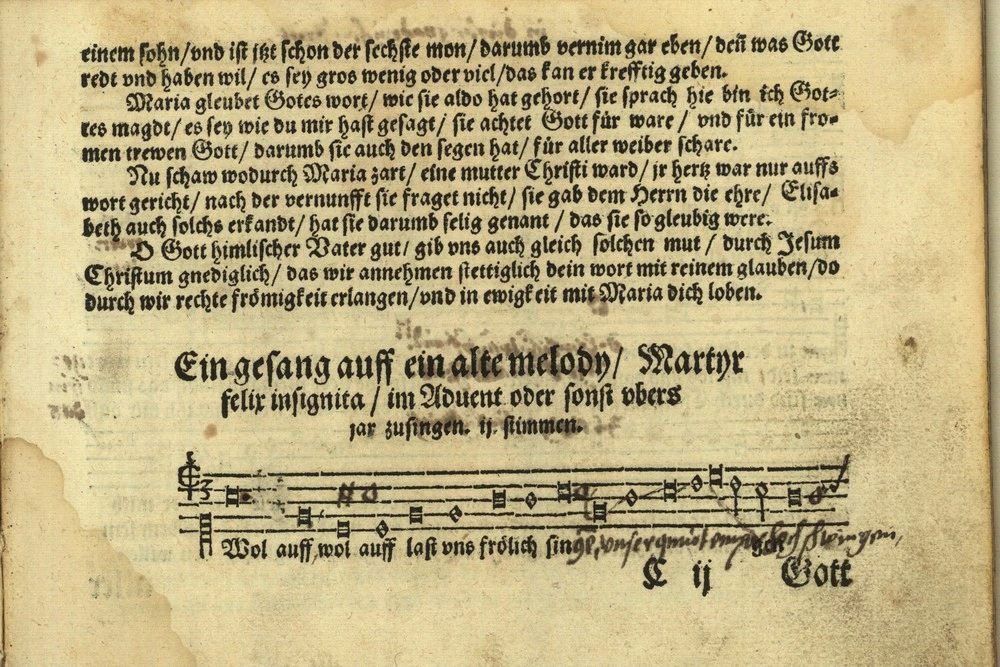

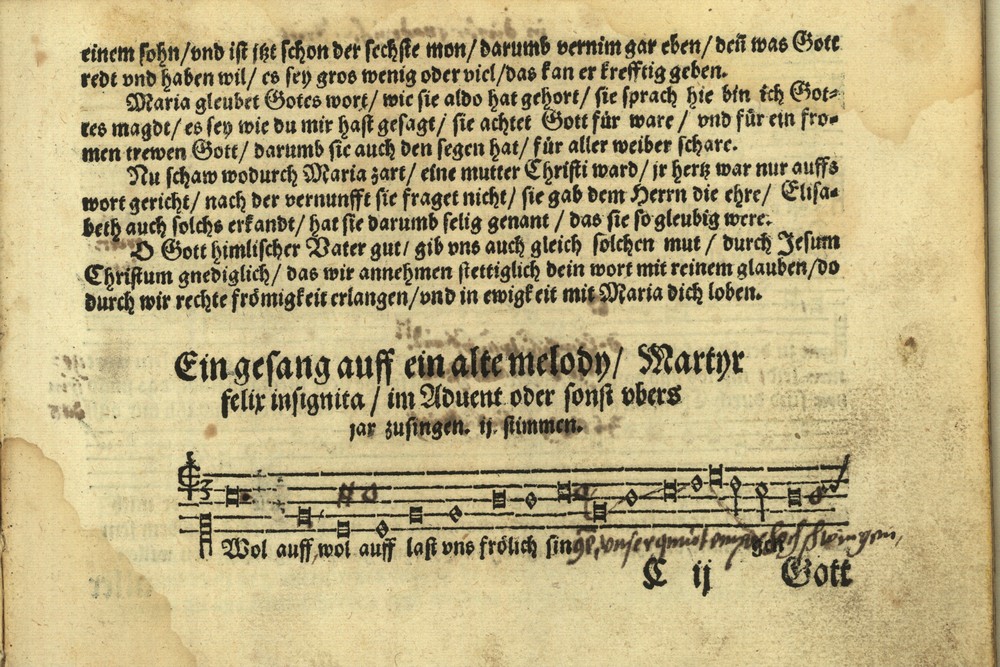

Uchovávání transformací: Valentin Triller a jeho Wolauff last uns frölich singen

Bez ohledu na hodnoty a identity, jaké mohly vyjadřovat, písně byly a stále jsou flexibilním médiem, jež mohlo sloužit zcela rozličným účelům. To ukazuje i následující příklad. V roce 1555 vydal Valentin Triller, luteránský pastor z malé vesnice v Dolnoslezském vojvodství, zpěvník nazvaný Ein Schlesich Singebüchlein, tedy „Slezský zpěvník“. Tato sbírka, určená pro slezské luteránské komunity, byla vytištěna ve Vratislavi a věnována Jiřímu II. Břežskému (1523–1586), luteránskému vévodovi Břežska a Lehnicka. Vévoda Jiří se mezi slezskými vévody těšil značné autoritě, díky čemuž mohl sehrát stěžejní roli v regulaci slezské evangelické církve. Jeho socha, vztyčená ještě za jeho života, tvoří dominantu hlavní brány na hradě v Brzegu v Dolním Slezsku (obrázek 3).

Mezi 145 hymny na německé texty Triller v Ein Schlesich Singebüchlein uveřejnil také několik polyfonních úprav, včetně jedné začínající na slova Wolauff last uns frölich singen („Nuže, pojďme vesele zpívat“, titulní foto). Titulní rubrika nám prozrazuje, že se jedná o „píseň na starou melodii Martir felix insignita“. Jak je uvedeno výše, Martir felix není nic jiného než alternativní incipit písně Martir Christi – a skutečně, Trillerova Wolauff last uns frölich singen je tím, co bychom nazvali kontrafaktum, tedy použití nového textu u již existující hudby. Analyzováním tohoto kontrafakta můžeme „číst“ dlouhou historii písně a zrekonstruovat její cesty přes hranice regionů i vyznání. Nejnápadnější rozdíl mezi Martir Christi a Wolauff last uns frölich singen je jazyk – latina oproti němčině. Trillerovu volbu němčiny lze vysvětlit snadno. Luteráni si vysoce cenili zpěvu v místních jazycích coby prostředku, díky kterému se mohli zapojit i ti věřící, kteří latině nerozuměli. Jelikož Trillerův hymnář byl explicitně určen slezským luteránům hovořícím převážně německy, nahrazení latinského textu německým bylo zcela přirozené. Kromě jazyka ovšem Triller změnil i obsah. Původní latinský text nepřeložil, ale napsal nový, ve kterém velebení mučedníka změnil ve velebení Boha a jeho Syna. Toto přeorientování obsahu hymnů od svatých přímo k samotnému Bohu je v procesu luteranizace častým úkazem: na uctívání svatých, obzvlášť těch, kteří se neobjevují v Písmu, se pohlíželo s velkou nevolí, neboť bylo vnímáno jako příklad projevu katolické a papežské pověrčivosti.

Z přísně hudebního hlediska si povšimneme mnoha rozdílů. Zaprvé je to notace. Černá mensurální notace, které si utrakvistické kruhy velmi považovaly, v luteránských komunitách takový význam neměla. Píseň tak byla vytištěna v standardní bílé mensurální notaci, v 16. století obvyklém způsobu hudebního zápisu. Části písně byly navíc transponovány, tedy zapsány od jiného tónu. Zatímco v utrakvistických pramenech se hlasy pohybují ve stejném rozsahu, v Trillerově verzi je vrchní hlas oproti spodnímu umístěn výše. Tato změna jistě odráží odlišné provozovací kontexty. V utrakvistických komunitách by píseň zpívali dospělí muži, jejichž hlasový rozsah se příliš neliší. V luteránských kostelích se oproti tomu zpěvu účastnili i chlapci, takže sbory byly složeny z různých hlasů – vysokého chlapeckého a středního až nízkého mužského.

V poslední řadě Trillerova verze vykazuje zcela odlišné chápání kontrapunktu; všechny rysy charakteristické pro utrakvistický „archaický“ repertoár, jako jsou paralelní perfektní konsonance a disonance, byly „zkroceny“ a píseň byla přepsána pomocí ortodoxnějšího způsobu vedení hlasů.

Verze Valentina Trillera tak poskytuje svědectví o zcela odlišném přístupu k hudební minulosti, který bychom mohli definovat jako „uchovávání transformací“. Zatímco utrakvističtí písaři to, co našli ve starších rukopisech, pozorně přepisovali, Valentin Triller se nevyhýbal přetváření písně, aby ji přizpůsobil novému provozovacímu kontextu. Tyto úpravy by se ovšem neměly chápat jako výraz nespokojenosti se starou Martir Christi. Naopak odhalují Trillerův úzký vztah k písni; místo toho, aby ji zavrhl, ji obnovil a tím udržel při životě. Tento úzký vztah si žádá vysvětlení. Proč si Valentin Triller pro svůj hymnus vybral tak starý „hudební model“ a proč jej uveřejnil v zpěvníku pro Slezany?

„Staré známé krásné melodie“

Triller naštěstí poskytl o svém editorském projektu mnoho informací v předmluvě ke zpěvníku. Přestože na trhu bylo již k dispozici množství zpěvníků jiných, Triller pociťoval potřebu „slezské“ sbírky, neboť ty ostatní obsahovaly „neznámé, cizorodé melodie a noty […], které ve Slezsku a místních kostelích nikdo nezná.“ Z předmluvy vyvěrá velmi živý obraz společného zpívání, kterému byl Triller coby kněz ve svém životě bezpochyby svědkem. Stěžoval si, že ony „neznámé, cizorodé melodie“ byly často zapsány ve špatných klíčích a notách, takže je nešlo správně zazpívat. To byl samozřejmě důsledek toho, že tyto melodie byly ve Slezsku cizí. Proto Triller posbíral a vytiskl „staré známé krásné melodie, které všichni v našich slezských obcích a komunitách znají“, čímž chtěl zabránit tomu, aby „zmizely a úplně se na ně zapomnělo.“

Zdá se, že Triller považoval repertoár ve svém hymnáři za „vytrácející se“ tradici, a v jeho slovech je patrný závan nostalgie. Martir Christi musela být jednou z oněch „starých známých krásných melodií“, které do slezské hudební tradice patřily, a právě proto k ní vytvořil kontrafaktum a uveřejnil ho v Ein Schlesich Singebüchlein. Přikláním se k názoru, že tento akt není v žádném rozporu se starší, českou verzí písně. I kdyby Martir Christi totiž byla složena v Čechách, „doma“ byla evidentně i ve Slezsku a dalších regionech střední Evropy. Původ písně můžeme určit filologickou analýzou, ovšem filologii nemůžeme vždy použít ke zkoumání kulturních identit. Valentin Triller považoval píseň za součást lokální, slezské tradice a o českých větvích v dějinách písně nemusel dokonce vůbec vědět. Ve výsledku Trillerův přístup k hudebně-liturgické minulosti působí jako směsice vzpomínání a zavrhování. Přestože byl loajálním luteránem, cíleně se vyhýbal luteránskému repertoáru chorálů (jak jim dnes říkáme a jak se zpívají), který budovaly tiskařské domy ve Wittenbergu a Norimberku – sice to byla nepopiratelná intelektuální centra luteránství, ovšem zároveň i místa, která Triller vnímal jako cizí. Aby „poslezštil“ zpěv v luteránských kostelech, obrátil se ke „starému“ katolickému repertoáru, jenž Slezskem koloval před reformací. Regionální slezská identita tak podnítila pěstování toho, co editor nazýval „lokální hudební minulostí.“

Analýzou těchto a dalších jevů se projekt Sound Memories snaží porozumět tomu, jak se hudba coby dočasné umění, které, abychom citovali slavný výrok Leonarda da Vinciho, umírá hned po svém stvoření, může stát „zvukovou vzpomínkou“, tedy něčím s dalekosáhlými následky. Když jsou „zvukové vzpomínky“ považovány za živoucí tradici a/nebo dědictví, pomáhají konstruovat a vyjednávat identity. Vzhledem k multidimenzionalitě hudebního média kombinujícího textový i hudební význam mohou pak „zvukové vzpomínky“ nenásilně pomáhat vytvářet identity rozličné – ve zde předložené případové studii utrakvistické a slezsko-luteránské.

„Zvukové vzpomínky“ se někdy mohou stát i „sporným dědictvím“, bojištěm mezi konkurenčními skupinami považujícími sebe sama za právoplatné dědice svých duchovních praotců, ovšem to už je téma pro jiný článek.

Přeložila Barbora Vacková

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]Tento seriál vzniká v rámci evropského projektu HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe, který řeší mezinárodní tým muzikologů pod vedením Prof. Karla Kügleho (Utrecht) v pěti akademických institucích (Univerzita Utrecht, Univerzita Cambridge, Univerzita Curych, Univerzita Karlova Praha, Polská akademie věd Varšava).

Více informací (včetně audio- a videozáznamů) najdete na webových stránkách projektu Sound Memories.[/block]

Vážení čtenáři, vzhledem k mezinárodnímu složení badatelského týmu mimořádně uveřejňujeme českou i anglickou variantu textu.

Memory and Tradition within the European Music Culture of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times

Preserving Sound Memories in Central Europe: The Polyphonic Song Martir Christi

In 1477, Johannes Tinctoris, a leading music theorist, wrote that ‘there does not exist a single piece of music, not composed within the last forty years, that is regarded by the learned as worth hearing.’ Much has been written about this statement, which is generally taken as compelling evidence that there was no awareness of the past in music prior to the nineteenth century. Textbook narratives of European music history are biased towards a teleological and ‘progressivist’ depiction of its development, grounded in the aesthetics of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – aesthetics many of us (as music lovers and consumers) probably share, whether consciously or not.

The research project Sound Memories aims to counteract this narrative by studying phenomena that exceed this evolutionary paradigm. We deal with an overarching theme, namely the cultivation of musical pasts in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, the means by which awareness of these pasts shaped cultural performances, and how the pasts were harnessed for political and religious objectives. In my contribution I would like to discuss one particularly telling example, a late-medieval song which circulated in different central European regions in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This song, usually known as Martir Christi, enjoyed a surprisingly long performance tradition, certainly exceeding Tinctoris’ limit of 40 years to which I referred above. The collation of different sources of this song allows us to suggest why such old music stood the test of time, and to analyse the means by which it was preserved, thus disclosing quite different approaches to the musical past.

Martir Christi

Martir Christi (sometimes known as Martir felix) is a two-voice polyphonic song. Its Latin sacred text suggests that it was performed at celebrations for martyr saints:

O martyr of Christ, who has been elevated to the highest honours for your chastity, and crowned with light. Now, gently spreading your voice, praise sweetly with songs the son of God the Father, the lily of purity, who chose for himself the holy martyr as his worthy servant.

The text does not make precise reference to one specific martyr, either by name or by recalling hagiographical details. This mirrors a desire for ‘liturgical flexibility’: by having a generic content, the same song could fit different ritual contexts, as long as they were dedicated to a martyr (male or female inflections would have been changed accordingly). It is also noteworthy that this song seems to speak about itself, when it invites singers to ‘praise sweetly with songs the son of God the Father’. Medieval sacred songs that thematise the act of singing are not uncommon, probably imitating the rhetorical patterns of the Holy Scriptures (think of the numerous musical references in the Psalms, for instance). At the same time, they might voice some kind of ‘corporate self-awareness’ of those responsible for the music.

Preserving by reproduction: Martir Christi in Utraquist manuscripts

Figure 1 reproduces the earliest source of this song, the Codex Speciálník, a paper manuscript copied most likely in Prague between 1485 and 1500, for the use of a Utraquist community, probably a brotherhood. Martir Christi was inscribed during the first copying phase of this manuscript, which was concluded by 1495. Note, however, that the date of copying and the date of composition do not necessarily coincide, and many hints suggest that this song was already quite old when it appeared in the Codex Speciálník.

Indeed, palaeographic and stylistic analysis confirm that it belongs to the so-called ‘archaic’ repertoire of the manuscript. The song was copied with black mensural notation, that is with all note values entirely black. This type of notation had not been used in central Europe for c. fifty years. Nonetheless, scribes in Prague and the rest of Bohemia still resorted to it for the traditional repertoire of the Utraquist Church. By using a peculiar and ‘archaic’ notation, the scribes were graphically representing the antiquity and venerability of a repertoire which was part of the cultual heritage of their Church.

From a stylistic point of view, the song similarly displays some features that are quite common in the so-called ‘archaic’ repertoire, such as parallel perfect consonances and unprepared dissonances. These features would not have been tolerated in ‘modern’ polyphony composed around 1500, but survived in this specific repertoire.

Although the features discussed suggest that Martir Christi was already quite old when it was copied in the Codex Speciálník, its momentum was not yet over, and we find it again in later handwritten and printed sources, thus proving that it was part of a living tradition. It is revealing to discuss two of these later sources, as they are specimen of different approaches to a shared musical past.

Let us first take a look at the so-called Chrudim Graduale (Figure 2), another Utraquist manuscript. It was copied thirty years later, in 1530, probably for a Utraquist community in Chrudim, eastern Bohemia. In a time in which the transmission of music was largely bound to the act of copying, it was very common for scribes to introduce variants and/or errors due to oversights or conscious rewritings. Nonetheless, if we compare the song Martir Christi as it appears in the Chrudim Graduale with its version in the Codex Speciálník, we are struck by the close relation between the two. Both sources transmit the song using the same black mensural notation. The text is the same, and the music is also basically the same, including the parallelisms and dissonances mentioned above. The precision with which the textual and musical content of Martir Christi was transmitted over the years exhibits a desire for a faithful preservation of a ‘traditional repertoire’. Evidently, Utraquist communities and their scribes attached great value to it. For decades, and indeed centuries, scribes transmitted the repertoire to which Martir Christi belonged retaining its defining features, notwithstanding the stylistic and notational ‘revolutions’ that took place in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. This is a very specific relation to the musical past, something I would like to define as ‘preserving by reproduction’.

Preserving by transformation: Valentin Triller’s Wolauff last uns frölich singen

Notwithstanding the values and identities that songs were able to carry, they were, and still are, a flexible medium which could serve quite different agendas, as the following example makes clear.

In 1555, Valentin Triller, the Lutheran pastor of a small village in Lower Silesia, published a hymnbook entitled Ein Schlesich singebüchlein, ‘a Silesian hymnbook’. This collection, intended for the use of Silesian Lutheran communities, was printed in Wroclaw, and was dedicated to Georg II of Brieg (1523-1586), the Lutheran duke of Brieg and Liegnitz. Duke Georg played a fundamental role in the regulation of the Silesian evangelical church, thanks to his leading political authority among Silesian dukes. His statue, erected when he was still alive, dominates the main gatehouse of Brzeg Castle, Lower Silesia (Figure 3).

Among the 145 German-texted hymns of Ein Schlesich singebüchlein, Triller also published several polyphonic settings,[1] including one beginning with the words Wolauff last uns frölich singen (‘Well then, let us sing merrily’, see title figure). The title rubric informs us that this is ‘a song on an old melody Martir felix insignita.’ As noted above, Martir felix is nothing but an alternative incipit of the song Martir Christi, and indeed the music of Triller’s hymn generally corresponds to the older version. Thus, Triller’s Wolauff last uns frölich singen is what we would call a contrafactum, a new text set to pre-existing music. Analysing this contrafactum, we can ‘read’ the long history of the song, reconstructing its ‘journeys’ across regional and confessional borders.

The most obvious difference between Martir Christi and Wolauff last uns frölich singen is the language, Latin vs German. Triller’s choice of German is easy to explain: Lutherans laid great value on vernacular singing, as a means to engage those faithful who could not understand Latin. Since Triller’s hymnbook explicitly targeted Silesian Lutherans, who were mostly German speaking, it was natural to substitute the Latin text with a German one. The change of language, however, also involved a change of content. Triller did not translate the Latin text: rather he wrote an entirely new text, turning the praise of a martyr into the praise of God and his Son. The ‘redirection’ of sacred hymns from saints to God himself is a common phenomenon in the transition to Lutheranism: the veneration of saints, especially those not based on the Holy Scriptures, was strongly frowned upon by the Reformation, since it was considered a Catholic and papist superstition.

From a strictly musical point of view, we notice many other differences. First of all, the notation. The black mensural notation, to which Utraquist circles attached great value, had no such meaning for Lutheran communities. Thus, the song was printed with the standard white mensural notation, the usual way of writing music in the sixteenth century. Additionally, the song parts were transposed, rewriting them at a different pitch. While in the Utraquist sources the parts have the same register, in Triller’s version the top part lies in a register higher than the low part. This modification certainly mirrors different performance contexts. In Utraquist communities the song would have been performed by adult men, who had voices of similar ranges. In Lutheran churches boys often took part in the musical performance, and choirs were therefore made up of different voices, the high register of boys and the mid-to-low registers of adult men.

Lastly, Triller’s version also exhibits a completely different understanding of counterpoint: all those features that are characteristic of the Utraquist ‘archaic’ repertoire, such as parallel perfect consonances and dissonances, were ‘tamed’ and rewritten into a more ‘orthodox’ voice leading.

Thus, Valentin Triller’s version testifies to a totally different approach to the musical past, something we could define as ‘preserving by transformation’. While Utraquist scribes carefully reproduced what they found in older manuscripts, Valentin Triller did not refrain from transforming the song in order to adapt it to a new performing context. Such modifications, however, are not to be interpreted as dissatisfaction with the old song Martir Christi. Quite they contrary, they reveal Triller’s attachment to it: instead of simply discarding it, he ‘re-created’ it to keep it alive. This attachment calls for an explanation. Why did Valentin Triller choose such an old song as the ‘musical model’ for his hymn, and why did he publish it in a hymnbook for Silesian communities?

‘Old familiar beautiful melodies’

Fortunately, Triller included information regarding his editorial project in the foreword of the hymnbook. Although many hymnbooks were already available on the market, he felt the need for a ‘Silesian’ collection because the other hymnbooks contained ‘foreign unfamiliar melodies and notes […] which are unknown in Silesian places and churches.’ From the foreword a very lively picture of communal singing emerges, something Triller certainly experienced in his daily life as a priest. He lamented that the ‘foreign unfamiliar melodies’ were often printed with wrong clefs and notes, so that it was impossible to sing them correctly. Obviously, this was a consequence of the fact that the melodies were unknown in Silesia. Thus, he collected and printed the ‘old familiar beautiful melodies which were known in our Silesian places and communities’ so as not to ‘disappear and [be] completely forgotten.’

Triller seems to consider the repertoire of his hymnbook as a ‘waning’ tradition, and he betrays a touch of nostalgia. Martir Christi must have been one of the ‘old familiar beautiful melodies’ that belonged to the Silesian musical tradition, and that is why Triller wrote a contrafactum on it and printed it in Ein Schlesich singebüchlein. I would argue that this is not in contradiction with the older Bohemian version of the song. Indeed, even if Martir Christi was composed in Bohemia, it was evidently also ‘at home’ in Silesia and in other central European regions. We can identify the origins of songs with philological analysis, but we cannot always apply philology to cultural identities. Valentin Triller considered the song to belong to a local, Silesian tradition, and he might have been simply unaware of the Bohemian strands in the history of the song.

All in all, Triller’s approach to the musical-liturgical past appears as a mixture of ‘remembering’ and ‘discarding’. Although he was a faithful Lutheran, he consciously avoided the Lutheran repertoire of chorales (as we now call them, as they are still sung today) that was established by printing houses in Wittenberg and Nuremberg; these were the unquestionable intellectual centres of Lutheranism, but also places that Triller saw as foreign. In order to ‘silesianise‘ Lutheran church singing, he relied on the ‘old’ Catholic repertoire which circulated in Silesia before the Reformation. Thus, a regional Silesian identity stirred the cultivation of what the editor considered a ‘local musical past.’

By analysing these and other phenomena, the Sound Memories project aims to understand how music, a temporal art that dies immediately after its creation (to quote Leonardo da Vinci’s famous statement), can become a ‘sound memory’ – sometimes with quite virulent consequences. When ‘sound memories’ are recognised as living tradition and/or heritage, they contribute to the construction and negotiation of identities. Given the multidimensionality of the musical medium combining textual and musical meaning, ‘sound memories’ can peacefully serve to construct different identities – in the case study portrayed here, a Utraquist and a Silesian Lutheran identity.

At times, ‘sound memories’ can become a ‘conflicted heritage’, a battlefield for competing groups that claim to be the legitimate heirs of their spiritual forefathers, but this is a topic for another article.

[1] See Antonio Chemotti, ed. The polyphonic hymns of Valentin Triller’s Ein Schlesich singebüchlein (Wrocław 1555), IS PAN 2019. Get an Open Access digital version of the book at https://epub.uni-regensburg.de/38328/.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]This series has been published as part of the European project HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, undertaken by an international team of musicologists led by Prof. Karl Kügle (Utrecht) in five academic institutions (Utrecht University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Zurich, the Charles University in Prague, and the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw).

Antonio Chemotti is a postdoctoral student in the Institute of Art at the Polish Academy of Sciences. In his research he occupies himself with the musical culture of early modern Silesia, and he is the author of a critical edition of Valentin Triller’s songbook Ein Schlesisch Singebüchlein (published in Warsaw in 2019).

More information (including audio and video recordings) see on Sound Memories project website.[/block]

This project has received funding from the H2020-EU.3.6 – SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307. The project Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe is financially supported by the HERA Joint Research Programme (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, PT-DLR, CAS, CNR, DASTI, ETAG, FCT, FNR, F.R.S.-FNRS, FWF, FWO, HAZU, IRC, LMT, MIZS, MINECO, NCN, NOW, RANNÍS, RCN, SNF, VIAA, VR and The European Community, SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307.

|

|

|