Zpívání v chmurných časech. Hudba v amsterdamském dvoře bekyní na počátku 17. století

Nizozemská reformace a Amsterdam

Když byl Amsterdam po několikaletém obléhání v roce 1578 dobyt gézy, stranou, která podporovala Viléma I. Oranžského a jeho boj za nezávislost od nadvlády Habsburků, správa města připadla do rukou kalvínům. To zasadilo bohaté středověké náboženské kultuře města smrtelnou ránu. Stejně jako v celé zemi byly amsterdamské kostely zabrány kalvinisty, kláštery se uzavřely a kněží a mniši buď odešli do ilegality, nebo byli nuceni město opustit. Jeptiškám a řádovým sestrám bylo dovoleno zůstat, ovšem jejich komunity již nesměly přijímat žádné novicky, a tak postupně zanikly. Katolické školy byly zakázány, katolická hierarchie vymizela a biskupům nebylo dovoleno se dále v Nizozemské republice zdržovat. V celé zemi zcela vymizela církevní infrastruktura. Největší náboženská instituce té doby se během několika let stala soukromou organizací. Velmi záhy se rozvinula podzemní katolická síť, takzvaná Nizozemská misie, jejímž prostřednictvím zůstávali katolíci ve styku. Kněží cestovali v utajení přes celou zemi převlečení za sedláky či tesaře. Tam, kam došli, se odehrávaly tajné bohoslužby a zvláště naléhavé mimořádné obřady jako křtiny, svatby a biřmování.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]For English version of the article please see below.[/block]

Na rozdíl od Anglie ovšem katolíkům v Nizozemské republice nehrozila smrt. Katolické bohoslužby byly povoleny za podmínky, že nebyly ani vidět, ani slyšet – jako kdyby se vůbec nekonaly. Vznikl tak nový druh kostelů – skryté kostely. Nejprve to byly kostely domácí. Katolíci otevírali svým rodinám a sousedům světnice, aby se v nich mohly konat bohoslužby. Místo pro mnoho lidí v nich nebylo. Když byl tedy zrovna k dispozici kněz, celý den se v nich konala jedna bohoslužba za druhou, jelikož současně se do místnosti nevešlo více než patnáct či dvacet věřících. Sloužit co největší počet bohoslužeb, aniž by se o nich dozvědělo služebnictvo nebo správce pozemků, bylo každopádně velmi náročné a v případě prozrazení katolíkům hrozila vysoká pokuta či dokonce vězení. Domácí kostely sloužily v Nizozemské republice jako místa katolického vyznání až do poloviny 17. století. Poté se katolíkům přeci jen trochu ulevilo. Byla jim opět dovolena výstavba skutečných kostelů a kaplí – pod podmínkou, že je nebylo poznat z ulice.

Několik katolických ostrůvků se v tomto rozbouřeném moři nicméně dalo nalézt: dvory bekyní. Bekyně byly zbožné laické ženy, které žily společně v jednom domě či v bekinážích, které tvořilo i několik tuctů domů. Bekináže mají dlouhou historii – od 13. století, kdy jsou poprvé zmíněny v písemných pramenech, až do roku 2014, kdy v Belgii zemřela poslední tradiční bekyně. Na rozdíl od jeptišek žily bekyně společně bez řeholních slibů. Po dobu svého setrvání v bekináži se zavázaly žít v počestnosti, řídit se stanovami bekináže a poslouchat svou matku představenou. Společenství ovšem mohly v jakékoliv chvíli opustit a směly si ponechat vlastní majetek, což v mnoha případech byly právě domy či pokoje dané bekináže. Z toho důvodu nemohly být bekináže rozpuštěny či vyvlastněny. Okolo roku 1600 byla amsterdamská bekináž katolickou oázou, nad kterou neměli městští radní téměř žádnou moc. I bekyně ovšem přišly o svůj kostel, který nakonec připadl v roce 1607 anglickým presbyteriánům. V důsledku toho vykonávaly bohoslužby v domácích kostelech na svém dvoře. Nová kaple byla v amsterdamské bekináži vysvěcena až v roce 1671.

Hudba pro domácí kostely

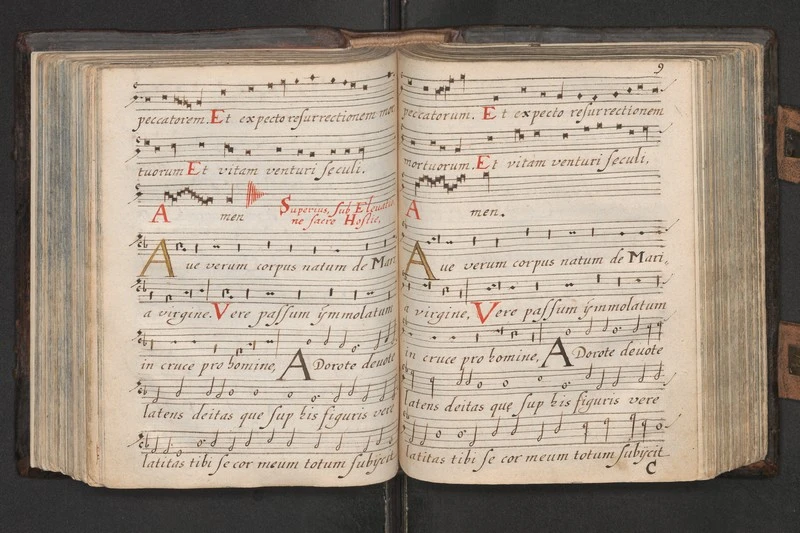

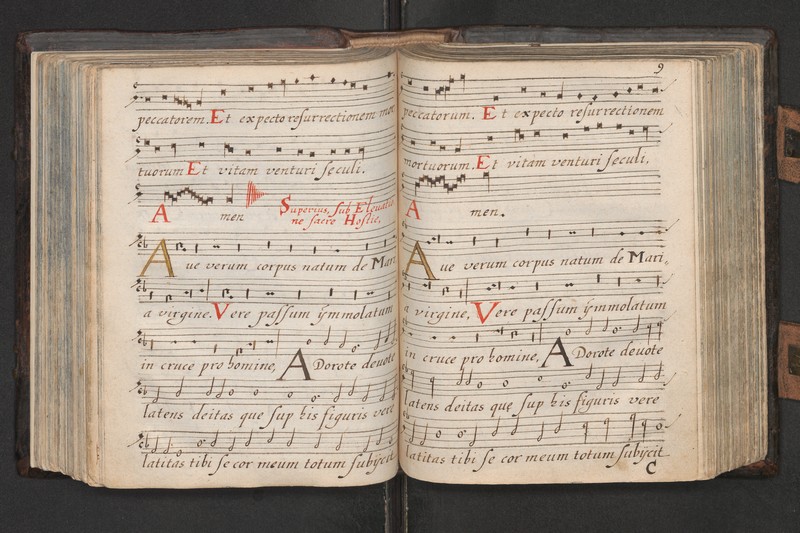

Okolo roku 1600 byly represe ovšem stále silné. Za takových podmínek se náboženské ceremonie značně lišily od těch v oficiálních církevních institucích, liturgie se nicméně sloužila. Jednou z mála dochovaných dobových liturgických knih pro domácí kostely je konvolut čtyř příruček uložený v univerzitní knihovně v Nijmegenu (na snímku výše). Jedná se o sbírku liturgických tisků vydaných v Antverpách a Mechelenu (dnešní Belgie) mezi lety 1589 a 1609 a později distribuovaných v severním Nizozemsku, pravděpodobně ve velkém nákladu. Tyto tisky obsahují základní liturgii pro domácí kostely v kalvínské zemi, jako byly například ty v amsterdamské bekináži. K tiskům byl připojen ještě ručně psaný dodatek, Cantuale na foliu 144. Zatímco tištěné části konvolutu jsou datované, rukopisné části ne. Vodoznaky na papíru s Cantuale nicméně poukazují na počátek 17. století, jelikož jsou identické s těmi, které lze nalézt na papíře tištěné příručky z roku 1609. Obsah ručně psané části je systematicky seřazen podle liturgického roku a hudebních žánrů. Zahrnuje gregoriánský chorál pro nešpory, několik zpěvů pro mešní ordinarium a jedno- až tříhlasé duchovní písně v latině a holandštině. Podle stanov amsterdamské bekináže byly bekyně povinovány sloužit nešpory společně v kostele, zatímco při dalších částech oficia (denních modliteb) se modlily samostatně. Když oficiální kostel bekyní již neexistoval, scházely se v některém z domácích kostelů bekináže.

Ženské sbory

Kromě jednohlasého zpěvu obsahuje Cantuale i polyfonní duchovní písně. Lze předpokládat, že v domácích kostelech byly zpívány oba žánry. Ovšem kým? V tradičním katolickém kostele byl toto úkol žáků a kněží. Ale katolické školy již neexistovaly, kněží se skrývali a kromě faráře se v bekináži žádný muž nevyskytoval. Lze se tak domnívat, že sbor tvořily samy bekyně. Sbory bekyní ostatně existovaly již ve středověku. Po složení přísných kvalifikačních zkoušek se hudebně nadaná bekyně mohla stát členkou sboru a dostávat za své hudební služby plat.[1] Lze si představit, že sbor tvořený obyvatelkami bekináže působil i v Amsterdamu, i když kromě zmiňované hudební knihy z počátku 17. století o tom žádné doklady nemáme.

Jak ale sborové zpívání v malých domácích kostelech probíhalo? Co se amsterdamské bekináže týče, tak opět přesně nevíme. Vytvořit si určitý obraz nám může pomoci další pramen, tentokrát z Haarlemu. V 17. století zde bylo sesbíráno více než dvě stě životopisů žen nazývaných „kloppen“ (klepadla) či „geesteijke maagden“ (duchovní panny).[2] Původ označení „kloppen“ není znám, ale může poukazovat na úkol těchto žen chodit od domu k domu a klepat na okna, aby informovaly katolické rodiny o možnosti navštívit bohoslužbu. Tyto panny se po reformaci vynořily po celém Nizozemí. V určitém ohledu se dají přirovnat k bekyním, ovšem na rozdíl od nich bydlely v menších společenstvích bez oficiálních stanov, blízko kněze nebo dokonce doma se svými rodinami. Někdy tyto panny obývaly bekináže společně s bekyněmi, například právě v Amsterdamu. V Haarlemu přebývaly společně v komunitě, která se dá k bekináži přirovnat. Některé z panen poskytovaly těm dalším své světnice, aby se v nich konaly bohoslužby. I ony měly sbor, zpívaly jednoduché vícehlasé písně. Podle životopisů pořádala sbormistryně, hudebně nadaná panna nebo vdova, každý týden zkoušky sboru ve svém obydlí. Zhruba dvacítka žen tu stála namačkána v malé místnosti; sednout si kvůli nedostatku místa nemohly. Zpívat byly nuceny potichu a se zavřenými okny, aby je nebylo slyšet ven na ulici. Za horkého letního počasí se tak mohlo zpěvačkám snadno udělat nevolno. I během bohoslužeb v obývacích pokojích musel být zpěv tlumený, aby ho neslyšeli kalvinisté venku. Bylo to, jak uvádí jeden ze životopisů, zpívání v „chmurných časech“. Jelikož zpívaly pouze ženy, tříhlasé písně se musely posadit velmi vysoko, aby nejnižší hlas (nazývaný „bassus“) zpěvačky vůbec měly šanci uzpívat. V důsledku toho byla poloha vrchního hlasu („superius“) velmi vysoká, a pravděpodobně právě proto býval tento hlas podpořen houslemi („violon“). Hrálo se i na další hudební nástroje, pokud byly k dispozici. Některé movité ženy měly ve svých obydlích malé varhany nebo klávesové nástroje, kterými bylo možné zpěv doprovodit.

Jak ale sborové zpívání v malých domácích kostelech probíhalo? Co se amsterdamské bekináže týče, tak opět přesně nevíme. Vytvořit si určitý obraz nám může pomoci další pramen, tentokrát z Haarlemu. V 17. století zde bylo sesbíráno více než dvě stě životopisů žen nazývaných „kloppen“ (klepadla) či „geesteijke maagden“ (duchovní panny).[2] Původ označení „kloppen“ není znám, ale může poukazovat na úkol těchto žen chodit od domu k domu a klepat na okna, aby informovaly katolické rodiny o možnosti navštívit bohoslužbu. Tyto panny se po reformaci vynořily po celém Nizozemí. V určitém ohledu se dají přirovnat k bekyním, ovšem na rozdíl od nich bydlely v menších společenstvích bez oficiálních stanov, blízko kněze nebo dokonce doma se svými rodinami. Někdy tyto panny obývaly bekináže společně s bekyněmi, například právě v Amsterdamu. V Haarlemu přebývaly společně v komunitě, která se dá k bekináži přirovnat. Některé z panen poskytovaly těm dalším své světnice, aby se v nich konaly bohoslužby. I ony měly sbor, zpívaly jednoduché vícehlasé písně. Podle životopisů pořádala sbormistryně, hudebně nadaná panna nebo vdova, každý týden zkoušky sboru ve svém obydlí. Zhruba dvacítka žen tu stála namačkána v malé místnosti; sednout si kvůli nedostatku místa nemohly. Zpívat byly nuceny potichu a se zavřenými okny, aby je nebylo slyšet ven na ulici. Za horkého letního počasí se tak mohlo zpěvačkám snadno udělat nevolno. I během bohoslužeb v obývacích pokojích musel být zpěv tlumený, aby ho neslyšeli kalvinisté venku. Bylo to, jak uvádí jeden ze životopisů, zpívání v „chmurných časech“. Jelikož zpívaly pouze ženy, tříhlasé písně se musely posadit velmi vysoko, aby nejnižší hlas (nazývaný „bassus“) zpěvačky vůbec měly šanci uzpívat. V důsledku toho byla poloha vrchního hlasu („superius“) velmi vysoká, a pravděpodobně právě proto býval tento hlas podpořen houslemi („violon“). Hrálo se i na další hudební nástroje, pokud byly k dispozici. Některé movité ženy měly ve svých obydlích malé varhany nebo klávesové nástroje, kterými bylo možné zpěv doprovodit.

Písně ze středověku?

Lze si představit, že zpěv se tímto způsobem provozoval nejen v Haarlemu, ale i v Amsterdamu. Na stránkách zmiňovaného ručně psaného zpěvníku lze nalézt dvou- a tříhlasé písně. Jejich úpravy jsou vcelku snadné a zvládnou je tak i zpěvačky bez vyššího klasického hudebního vzdělání. Některé z textů těchto písní pochází již z 15. či raného 16. století, kdy byly zapsány do zpěvníků devotio moderna. Toto náboženské hnutí „moderní zbožnost“ hrálo v duchovním životě Nizozemska 15. a 16. století velkou roli a rozšířilo se i na území dnešního Německa, Belgie a severní Francie. Kromě dalších svědectví o hnutí se dochovaly i jeho liturgické knihy a zpěvníky. Po reformaci ovšem jeho sídla téměř vymizela.

Zatímco některé z písňových textů v amsterdamském Cantuale mají svůj původ právě v tomto hnutí, hudba ne. Na rozdíl od zpěvníků 15. století se v rukopisu bekináže kombinovaly dvouhlasé úpravy písní s relativně komplikovanými formálními hudebními strukturami, jako je například používání hned několika refrénů v rámci jediné písně. Bohatou škálu hudebních možností lze pozorovat i v notaci; pro označení různých druhů hudby se užívaly dokonce tři různé typy notace (titulní foto). Ty „nejmodernější“ písně jsou určeny k pozdvihování a používají dokonce linku generálbasu, což byl v 16. století velmi čerstvý vynález. Mnoho jednoduchých vícehlasých úprav zní sice dost středověce, ale jsou nové. V amsterdamské bekináži se tak středověké texty kombinovaly s hudbou a hudebními strukturami raného novověku.

[1] Walter Simons, “Beguines, Liturgy and Music in the Middle Ages: An Exploration”, in: Peter Mannaerts (ed.), Beghinae in cantu instructae. Musical patrimony from Flemish beguinages (Middle Ages – Late 18th C.), Turnhout 2009, 15-25.

[2] Životopisy jsou přepsány jako dodatek CD-romu Joke Spaans, De Levens der Maechden. Het verhaal van een religieuze vrouwengemeenschap in de eerste helft van de zeventiende eeuw. Hilversum 2012.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]Tento seriál vzniká v rámci evropského projektu HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe, který řeší mezinárodní tým muzikologů pod vedením Prof. Karla Kügleho (Utrecht) v pěti akademických institucích (Univerzita Utrecht, Univerzita Cambridge, Univerzita Curych, Univerzita Karlova Praha, Polská akademie věd Varšava).

Ulrike Hascher-Burger je přidružená badatelka v Ústavu pro výzkum kultury na Univerzitě v Utrechtu a v rámci projektu Sound Memories zkoumá hudební kulturu v domácích kostelech Nizozemské republiky na začátku 17. století. Partner projektu, soubor Trigon Ensemble vedený Margot Kalse, šíří hudbu bekyňského rukopisu ve speciální koncertní řadě v Nizozemí a Německu.

Více informací (včetně audio- a videozáznamů) najdete na webových stránkách projektu Sound Memories.[/block]

Vážení čtenáři, vzhledem k mezinárodnímu složení badatelského týmu mimořádně uveřejňujeme českou i anglickou variantu textu.

Memory and Tradition within the European Music Culture of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times

Singing in ‘dreary times’. Music from the Amsterdam court beguinage in the early 17th century

The Dutch Reformation and Amsterdam

When, after being besieged for several years, Amsterdam was captured in 1578 by the “geuzen”, the party which supported the Prince of Orange in his struggle for independence from the Habsburg Monarchy, the city council was replaced by Calvinist governance. This resulted in a deathblow to the rich medieval religious culture of the city. As in the whole country, in Amsterdam, churches were taken by the Calvinists, monasteries were closed, and priests and monks went underground or had to leave the town. Nuns and sisters were allowed to stay, but as their communities were no longer permitted to accept novices they died out. Catholic schools were banned, the catholic hierarchy vanished, and bishops were not allowed to stay in the Dutch Republic. In the whole country the religious infrastructure had disappeared, and within a few years, the biggest religious institution turned into a private organization. An underground Catholic network, the ‘Dutch mission’, was quickly established through which Catholics kept in touch with each other. Priests travelled through the country undercover, masquerading as farmers or carpenters and where they popped up, secret services were organized and urgent special events such as baptisms, weddings, and confirmations took place.

Unlike in England, Catholics in the Dutch Republic were not threatened with death. Catholic services were allowed on the condition that nothing could be seen or heard, and that when they took place it was as though they had not been celebrated. A special kind of church arose: the hidden church, which in the beginning, were house churches. Catholics allowed the use of their private living rooms for services with their families and neighbors. As space was limited – no more than c. 15-20 people could attend at one time – when a priest was available, the whole day was spent celebrating one service after another. It was a challenge to celebrate as many services as possible without being discovered by the servants of the bailiff and imposed with a severe fine or prison sentence. House churches served as locations for Catholic worship in the Dutch Republic up until the middle of the 17th century, after which life for Catholics became just a bit easier. They were allowed to build real churches and chapels again, as long as these buildings could not be recognized from the street.

Yet, there were some small islands in this ferocious sea: the court beguinages. Beguines were devout lay women who lived together in a house or in a court beguinage which could comprise dozens of houses. Beguinages had a long history, from the 13th century, when beguines are mentioned in written sources for the first time, right up until 2014, when the last traditional beguine died in Belgium. Different from nuns, beguines lived together without vows. During their stay at the beguinage they promised to live in chastity and to be obedient to the statutes and to the Reverend Mother of the community. However, they could leave the community at any moment and were allowed to keep their own belongings. In many cases they owned a house or a room in the beguinage, and for this reason, beguinages could not be dissolved or expropriated. Around 1600, the beguinage in Amsterdam was a Catholic oasis where the city council did not have much influence. Nevertheless, the beguines, too, lost their church, which was finally given to the English Presbyterians in 1607. As a result, the beguines celebrated in house churches in their court. Only in 1671 was a new chapel consecrated in the Amsterdam beguinage.

Music for house churches

Around 1600 however, the situation still was quite oppressive. Nevertheless, the liturgy was celebrated, and under such circumstances, divine services were quite different from services in an official institutional church. One of the few contemporaneous liturgical books for house churches preserved today is a convolute of four booklets in the university library of Nijmegen,[1] a collection of liturgical prints published in Antwerp and Mechelen (today Belgium) between 1589 and 1609, and then distributed in the Northern Netherlands, possibly in a larger edition. These prints contain the basic liturgy for Catholic house churches in the Calvinistic Republic as were housed in the Amsterdam beguinage. A handwritten appendix, a Cantuale of 144 folia, was added to these prints. While the printed parts of the convolute are dated, the manuscript parts are not. The watermarks of the paper of the Cantuale, however, point to the beginning of the 17th century as they are identical to those of the paper used for a booklet known to have been printed in 1609. This handwritten part is systematically ordered according to the liturgical year and to musical genres. It contains a large group of Gregorian chants for vespers, some chants for the mass ordinary, and religious songs for one to three parts in Latin and Dutch. According to the statutes of the Amsterdam beguinage, the beguines were obliged to celebrate vespers together in the church (or, when there was no official beguine church, in one of the house churches), while they attended the other office services individually.

Women’s choirs

Beside the monophonic chant, the Cantuale also contains polyphonic religious songs. It can be assumed that both genres were sung in the house churches as well. But by whom? In the traditional Catholic church this was the task of schoolboys and priests. But Catholic schools didn’t exist any longer, and priests were hidden. Besides the rector of the beguinage, there were no males in the complex. It can therefore be assumed that the beguines themselves formed a choir. Beguine choirs were known in the Middle Ages: after a severe qualifying examination, a musically gifted beguine could become a choir beguine who was payed for her musical services.[2] In Amsterdam, too, a choir of inhabitants of the beguinage is conceivable, even though we have no further information about this than the music book from the early 17th century.

But how did a choir sing in a small house church? Again, we don’t know exactly for the Amsterdam beguinage. However, another source, from the city of Haarlem, offers an impression. More than 200 biographies of women, called ‘kloppen’ (knockers) or ‘geestelijke maagden’ (spiritual virgins), were collected during the 17th century.[3] The origin of the term ‘kloppen’ is not known, although it might point to their task to inform Catholic families of the possibility of joining a service by going from house to house knocking on the windows. These virgins appeared after the Reformation in the whole of the Dutch Republic. In some regards they can be compared with beguines, although they lived in smaller communities without official statutes and around a priest, or even at home with their families. Sometimes these virgins lived in beguinages together with beguines, for instance in Amsterdam. In Haarlem these virgins lived together in a community that can be compared to a beguinage, and again some offered their living rooms to celebrate services. These virgins had a choir, too, and they sung simple polyphonic songs. According to the biographies, the choirmaster, a musically gifted virgin or widow, offered weekly choir rehearsals in her own living room. Around 20 women stood crammed in a small room with not enough space to sit down. They had to sing quietly and with the windows shut in order to not be heard from the street. In summer, with warm weather, singers could become unwell. During services in house churches, singing also had to be muted so that it was not heard by Calvinists on the street, and is mentioned in one of the biographies as singing in “dreary times”. With only women singing, the three-part songs had to be intoned quite high so that the lowest part – called ‘bassus’ – could be sung by women with low voices. As a result, the position of the upper voice – ‘superius’ – was quite high, probably the reason why a violin (‘violon’) was used to support this part. Other musical instruments were played, too, if they were available. Some rich women had a small organ or a keyboard in their living room which could be used to support the singing. This type of singing practice is imaginable not only in Haarlem, but also in Amsterdam.

Songs from the middle ages?

The hand-written songbook contains two- and three-part songs. The settings are quite simple and could be performed by singers without a high standard of musical education. Some of the song texts are from the 15th and early 16th centuries, when they were transmitted in songbooks of the ‘Devotio moderna’ (the Modern Devotion), a religious movement that spiritually dominated in the Netherlands in the 15th and 16th centuries. This movement spread over a territory that today comprises Germany, Belgium, and Northern France. From this movement, among other testimonies, liturgical books and songbooks have survived. After the Reformation the houses of this movement almost completely vanished.

While some of the song texts in the Amsterdam Cantuale reach back to this movement, the music does not. Different from the 15th century songbooks, in the manuscript from the beguinage, simple two-part settings were combined with quite complicated formal structures, even using several refrains in one song. This richness of musical possibilities also can be seen in the music notation, when three different types of notation were used to indicate different types of music (see on title picture). The most ‘modern’ songs are those for elevation which even use a general bass line – a quite new invention in the early 17th century. Nevertheless, many of the simple polyphonic settings sound quite medieval, although they are new. At the Amsterdam beguinage, medieval texts were combined with early modern music and musical structures.

[1] Nijmegen, University Library, Hs 402. More information on Musica Devota: https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:116182/tab/2 => Übersicht => Nijmegen Hs 402.

[2] Walter Simons, “Beguines, Liturgy and Music in the Middle Ages: An Exploration”, in: Peter Mannaerts (ed.), Beghinae in cantu instructae. Musical patrimony from Flemish beguinages (Middle Ages – Late 18th C.), Turnhout 2009, 15-25.

[3] The bibliographies are transcribed as an appendix on a cd-rom by Joke Spaans, De Levens der Maechden. Het verhaal van een religieuze vrouwengemeenschap in de eerste helft van de zeventiende eeuw. Hilversum 2012.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]This series has been published as part of the European project HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, undertaken by an international team of musicologists led by Prof. Karl Kügle (Utrecht) in five academic institutions (Utrecht University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Zurich, the Charles University in Prague, and the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw).

Ulrike Hascher-Burger is an associate researcher in the Institute for Cultural Inquiry at Utrecht University. For the Sound Memories project she studies the musical culture of house churches in the Dutch Republic at the start of the seventeenth century. A partner of the project, Trigon Ensemble dir. Margot Kalse, shares music from a beguine manuscript in a special concert series in Germany and the Low Countries.

More information (including audio and video recordings) see on Sound Memories project website.[/block]

This project has received funding from the H2020-EU.3.6 – SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307. The project Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe is financially supported by the HERA Joint Research Programme (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, PT-DLR, CAS, CNR, DASTI, ETAG, FCT, FNR, F.R.S.-FNRS, FWF, FWO, HAZU, IRC, LMT, MIZS, MINECO, NCN, NOW, RANNÍS, RCN, SNF, VIAA, VR and The European Community, SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307.

|

|

|