[block background=“#e5e5e5″]For English version of the article please see below.[/block]

David Chytraeus a význam minulosti pro luteránskou hudbu a liturgii

Církevní pořádky a agendy (speciální knihy regulující užívání hudby v liturgii), poskytují vhled to luteránského chápání hudebních dějin a způsobu, jakým se používaly historické argumenty k odůvodnění přítomnosti hudby v kostele. Právě díky těmto legitimizujícím argumentům byla hudba v luteránských kostelích, na rozdíl od těch katolických, považována za oprávněnou praxi, která není v žádném rozporu s Biblí.

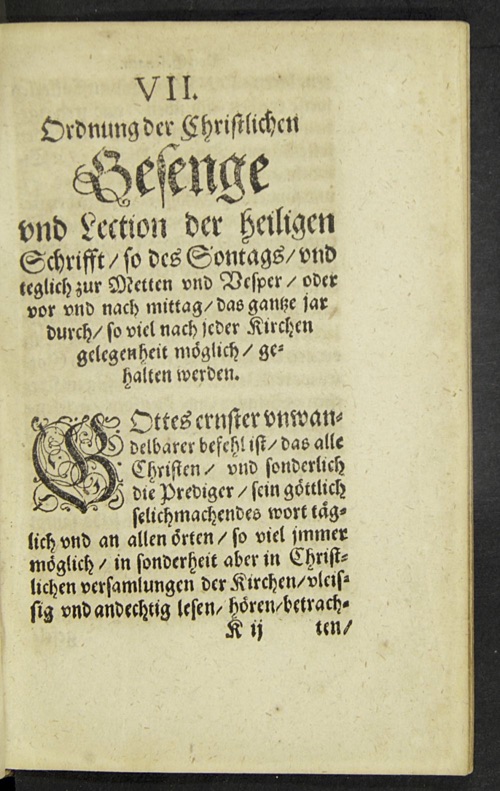

Jednou takovou knihou, která vymezuje pravidla pro užívání hudby v liturgii, je agenda Davida Chytraea z roku 1578. Tato neobyčejně podrobná agenda poskytuje cenný vhled do luteránského chápání hudebních dějin, roli hudby ve vytváření identity denominace a způsobů, jak sebe sama vnímá, i role minulosti v luteránské hudbě a liturgii. V předmluvách (jak k agendě jako celku, tak k jejím jednotlivým oddílům), osvětluje Chytraeus luteránskou hudbu a pohled na hudební dějiny. Jeho chápání hudby a její minulosti vykazuje značné paralely s jeho pojímáním historie jako takové, především, co se týče kombinace teologického argumentu a humanistické historiografie.

David Chytraeus a jeho agenda – historický kontext

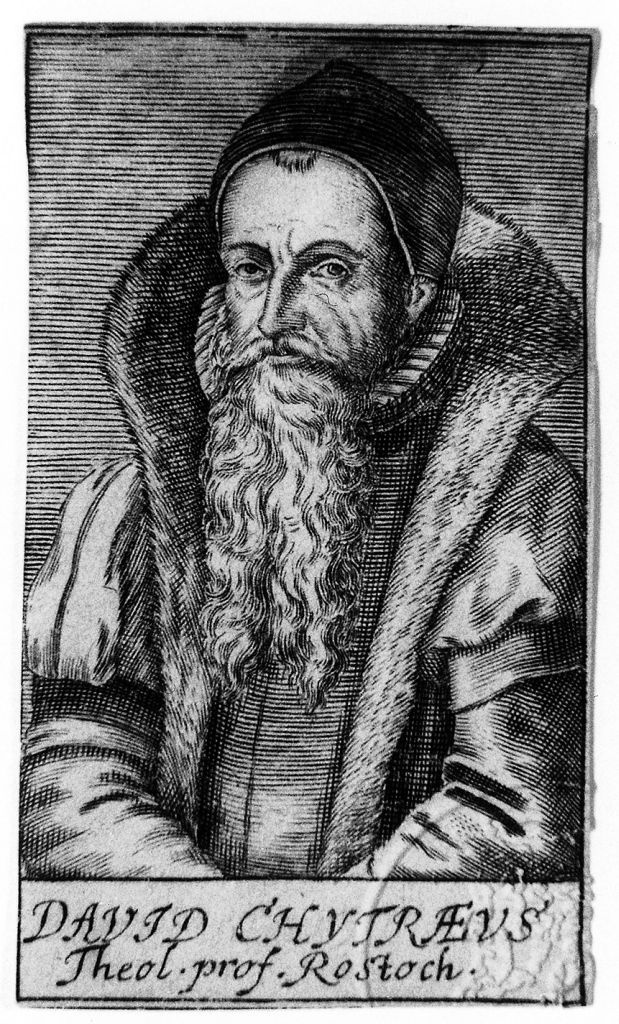

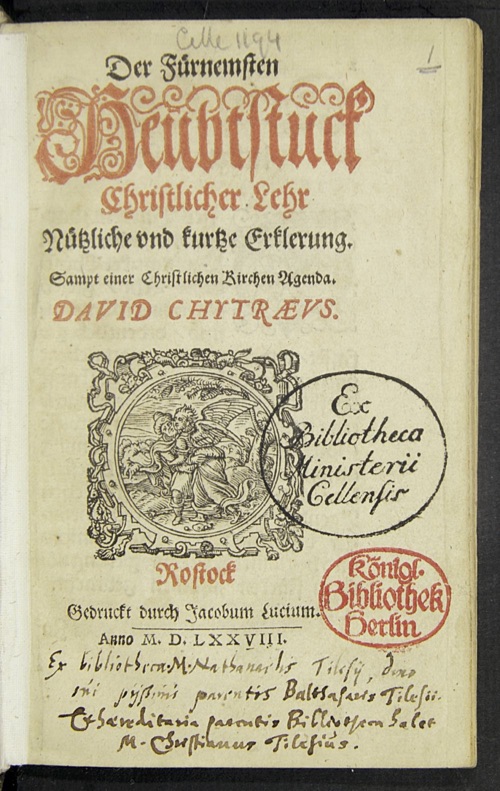

David Chytraeus byl luteránský teolog a historik. Jeho prvním exkurzem do hudební historie byl komentář ke knihám Mojžíšovým In Deuteronomium Mosis Enarratio z roku 1575, ve kterém představil v té době novou historiografickou perspektivu. Chytraeův zájem o hudební minulost se odráží i v jeho agendě z roku 1578. Tato agenda byla vydána jako dodatek k německému překladu jeho katechismu. Tento katechismus, poprvé vydaný v roce 1554 v latině, byl jedním z nejrozšířenějších katechetických naučných spisů té doby. Představoval úvod do křesťanské doktríny pro pokročilé studenty již obeznámené s katechismem Lutherovým.

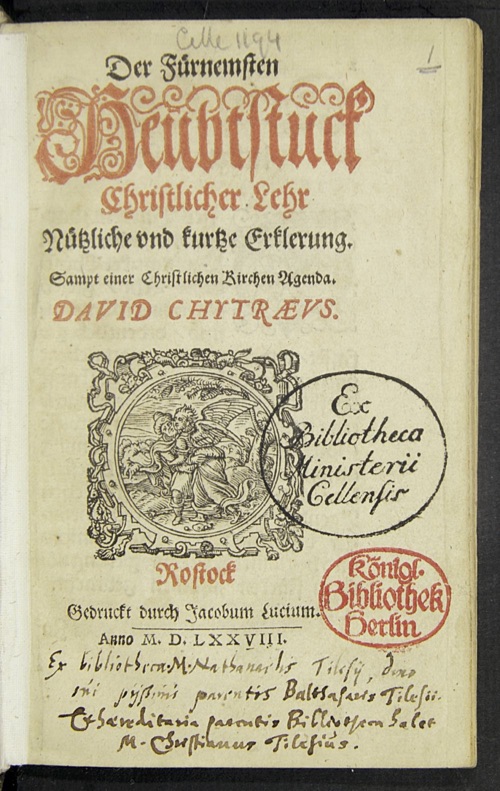

K vydání Chytraeovy agendy coby dodatku k jeho vlastnímu katechismu došlo díky historickým událostem týkajícím se Chytraeovy reformační mise v Rakouském arcivévodství. V roce 1568 udělil císař Maxmilián II. náboženskou svobodu rakouské luteránské komunitě. V tom samém roce byl pozván i Chytraeus, aby sepsal církevní pořádek, pořádek pro superintendenci a konsistorium, vysvětlení Augsburského vyznání (což byl dogmatický spis) a pořádek pro svěcení farářů. Tyto dokumenty měly regulovat aktivity luteránské církve v Rakouském arcivévodství, nicméně v Rakousku nebyly ve svém celku nikdy vydány. Kompletní soubor textů byl publikován poprvé až v roce 1578 v Rostocku a zahrnoval Heubstuck christlicher Lehr (rozšířený překlad Chytraeova latinského katechismu zmíněného výše), agendu založenou na rakouské verzi z roku 1571, již zmiňované pořádky a liturgický kalendář.

Hudba a liturgie v agendě z roku 1578 – tradice a hudební minulost

Již předmluva k agendě obsahuje důležité poznatky týkající se Chytraeových názorů na liturgickou hudbu a její minulost. Zpěv podle Chytraea patří mezi ta pravidla a obřady, které nenařídil explicitně Bůh, ale které zavedli lidé, aby učinili doktrínu srozumitelnější a posílili víru. Zpěv je tak považován za jednu z takzvaných „nepovinných záležitostí“ (adiafora), se kterými mohlo být zacházeno podle různých okolností rozličně. Chytraeus toleruje adiafora (včetně církevní hudby) pod podmínkou, že nejsou v rozporu s Biblí, především v případech, kdy Písmo nepromlouvá jednoznačně. Hudba, ač pouze jako jedna z adiafor, je tak legitimizována jako povolená činnost. Chytraeus si nepřál homogenizovat liturgickou praxi ve všech luteránských kostelech. Naopak se, na doporučení článků Augsburského vyznání, zasazoval o udržování lokálních tradic, pokud nejsou v rozporu s Biblí.

Chytraeus ve svých pořádcích pro zpěv popisuje užívání jednohlasé hudby při různých bohoslužbách. Hudbu legitimizuje výčtem úryvků z Bible, které označují zpěv za formu velebení Boha. Typické pro luteránské myšlení, obzvláště po Melanchthonovi, je, že hudba je pokládána za dar Boha lidstvu coby prostředek teologického poučení, který má tlumočit důležité články víry a upevnit je v lidské paměti. Text, který hudba přináší, je tedy zásadním prvkem legitimizace církevního zpěvu, jenž má napomáhat lepšímu porozumění božímu slovu. Chytraeus se následně obrací k často zhudebňovaným biblickým textům označovaným v Bibli za písně. Uvádí Sanctus zmiňované v Knize Izaiáš, Gloria z Lukášova evangelia, píseň Veliké a podivuhodné jsou tvé skutky ze Zjevení Janova, starozákonní písně Mojžíše, Debory, Báraka, Hany, Izaiáše, Ezechiela, Jonáše a Abakuka a samozřejmě Davidovy žalmy. Z Nového zákona zmiňuje mariánské Magnificat, Zachariášovo Benedictus a Simeonovo Nunc dimittis. Tyto příklady podporují historický argument naznačený výše. Hudba v kostele je legitimizována, jelikož je – alespoň tedy její textová část – zaznamenána v Bibli. Jiným typům hudby se Chytraeus nevěnuje, čímž je veškerá pozornost soustředěna na teologický argument o Bohu coby původci veškeré hudby.

Další paralelou s luteránskou historickou interpretací biblických časů a starověké církve coby ideálů, které později lidskými vlivy upadaly právě až do Lutherovy reformy, je Chytraeovo pozitivní hodnocení biskupů starověké církve jako skladatelů duchovní hudby. Zmiňuje Ambrose, Fortunata a Prudentia. O Lutherovi a Jednotě bratrské, jejíž repertoár, který Luther sám velmi obdivoval, byl zčásti převzat do luteránské hymnografie, hovoří jako o soudobých autorech hudby, která se vyrovná té ideální, jak je reprezentována Biblí a starověkou církví. Lutherův postoj k hudbě se tak značně podobá jeho přístupu k církevní historii coby procesu vykoupení po dlouhém období úpadku. V tomto ohledu vykazuje Chytraeův krátký text o hudbě rysy typické pro tehdejší historickou argumentaci.

Hudební minulost zde není historií v moderním slova smyslu. Naopak, historický argument není využit za účelem vytváření historiografického přehledu, ale kvůli teologické legitimizaci hudby a idejí reprezentovaných luteránskou konfesí. Zásadní roli historických argumentů v tomto kontextu lze přičíst humanistickým ideálům doby. Chytraeova předmluva prozrazuje jeho povědomí o minulosti a hudebních dějinách navzdory inherentním limitům předmluvy coby žánru, který ze své podstaty nenabízí prostor pro větší rozvedení tématu.

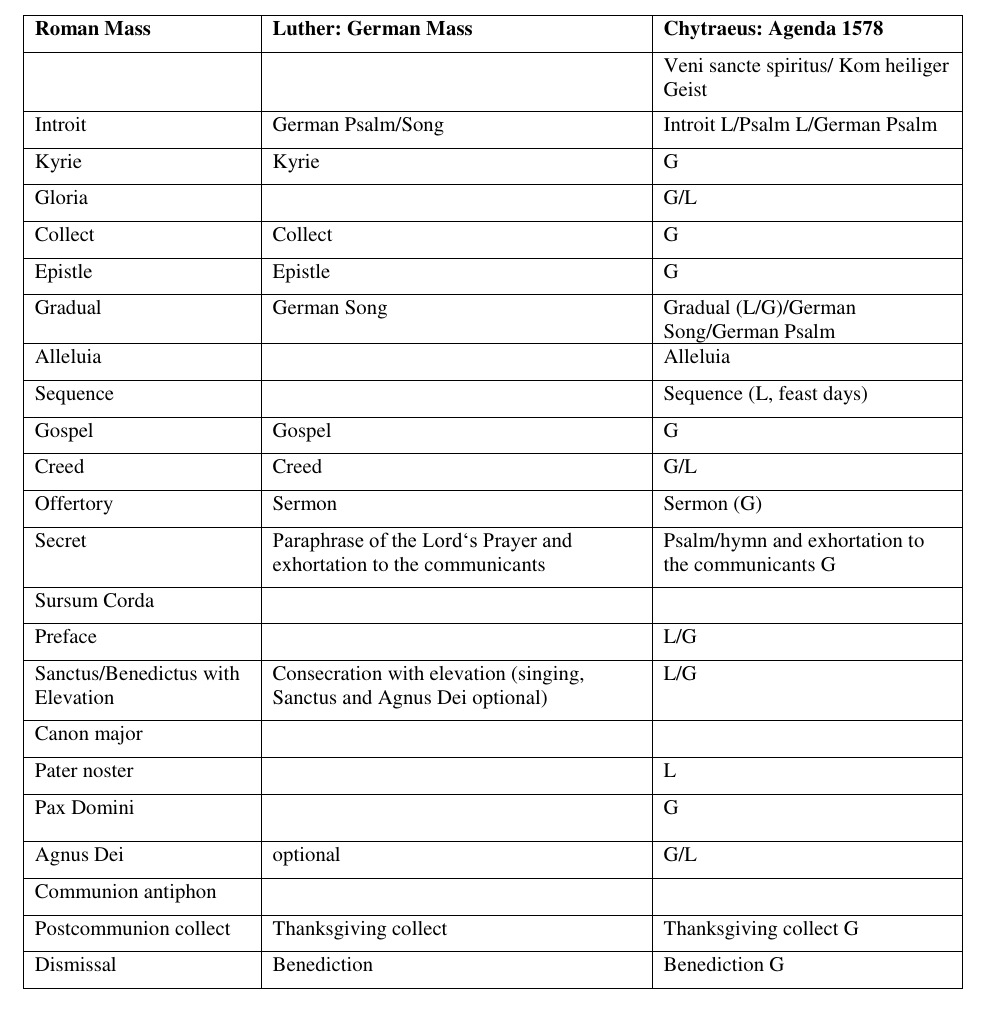

Významnou roli, kterou minulost hraje pro hudbu i liturgii, lze pozorovat i v Chytraeově ordináriu k německé mši obsaženém v jeho agendě. V porovnání s všeobecně známým ordináriem ke mši luteránské vykazuje toto ordináriům několik mimořádně „konzervativních“ charakteristik.

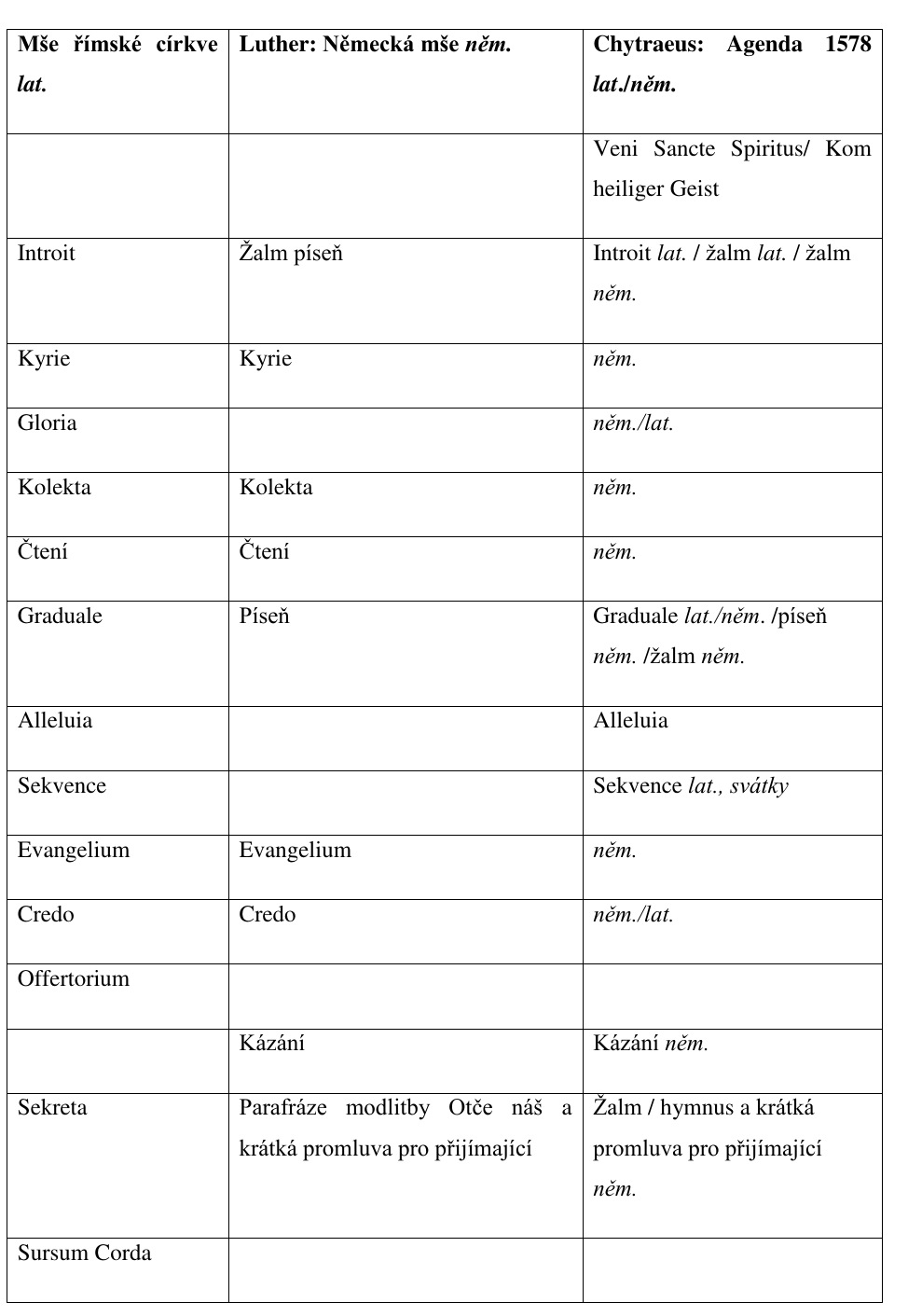

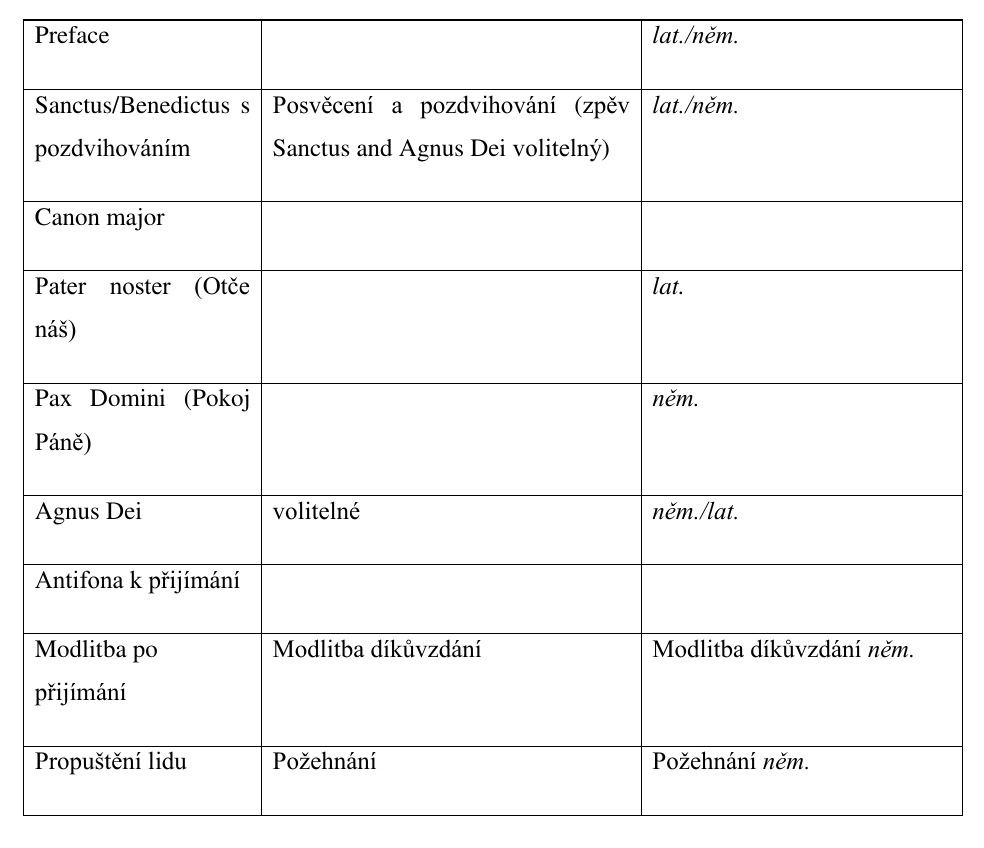

Tabulka 1: Srovnání mešního řádu mezi římským ritem, Lutherovou Německou mší a Agendou Davida Chytraea

Na rozdíl od Luthera v jeho Německé mši (1526) zahajuje Chytraeus mši Veni sancte spiritus zpívaným v němčině nebo latině, což je postup, který lze v protestantských mešních formulářích nalézt často. Kyrie, které by podle Chytraea mělo být v němčině, lze zpívat polyfonně. Chytraeus výslovně povoluje tropování Kyrie, zatímco Luther ve své Německé mši předepisuje Kyrie třikrát opakovat. Tato tropovaná Kyrie – tedy Kyrie s textovým či hudebním rozšířením – dokládají kontinuitu lokálních zvyků s těmi předreformačními. Alleluia a sekvence na postní dny jsou v Chytraeově agendě zachovány, ačkoliv v Lutherově Německé mši se už nevyskytují. Chytraeova mše si ponechává i Gloria, Graduale, prefaci, latinské Pater noster a německé Pax Domini, které vycházejí z římského ritu.

I když předepisuje většinu částí mše v němčině a vynechává ty části římského ritu, které teologicky neodpovídají luteránskému chápání mše, Chytraeův mešní formulář se římskému modelu blízce podobá. Tento úzký vztah s předreformační mší není specifikem Chytraeovy agendy; spíše vypovídá o obecných luteránských liturgických a hudebních zvycích a důležitosti přikládané lokálním tradicím a jejich udržování.

Chytraeus také ustanovuje pravidla pro hudbu mešního propria. Pro období mezi Vánoci a Očišťováním Panny Marie předepisuje německé luteránské hymny, latinské koledy a německé žalmové písně. Není bez zajímavosti, že luteránské hymny nazývá doslovně „alte Geseng“, tedy „staré písně“, když prohlašuje, že starý písňový repertoár se má upřednostňovat před jakýmikoliv novějšími německými hymny nebo úpravami Lutherových písní. Chytraeus tak pokládá repertoár první poloviny 16. století za „starý“ a upřednostňuje právě tuto starší hudbu před soudobým repertoárem.

Pro následující neděle církevního roku Chytraeus předepisuje německé hymny nebo žalmové písně, německé Magnificat a Benedictus. Za povšimnutí stojí, že většina těchto hymnů a písní je buď napsána přímo Lutherem, nebo pochází z raných reformačních kancionálů, jako jsou Achtliederbuch či Erfurt Enchiridion. To samé platí pro hudbu, kterou Chytraeus určuje pro období od Velikonoc do Nanebevstoupení Páně – přidává pouze německé Credo a litanie. Pro svátek Nejsvětější Trojice připojuje ještě německou verzi ambroziánských a atanášských písní, stejně tak jako jedinou latinskou píseň pro dvacátou třetí neděli po svátku Nejsvětější Trojice.

Chytraeova agenda předepisuje pro luteránské bohoslužby během liturgického roku především německé hymny. Výběr jazyka je motivován přesvědčením, že, jak Chytraeus uvádí v předmluvě, by písním měli rozumět i nevzdělání lidé. Latinský repertoár je nicméně rovněž přítomen, což je pro luteránský kontext typické. Co se jeho týče, odkazuje Chytraeus na Psalmodii Lucase Lossia poprvé vydanou v roce 1553. Psalmodie byla široce užívaným luteránským kancionálem obsahujícím veškerou latinskou liturgickou hudbu, která byla během církevního roku potřebná.

Stejně jako mnozí další doporučuje Chytraeus sekvence v latině. Přestože Luther omezil jejich počet na tři (Sancti spiritus assit nobis gratia, Veni sancte spiritus, Grates nunc omnes), Chytraeus jich jmenuje daleko více včetně latinských sekvencí pro Velikonoce, Letnice, svátek svaté Marie Magdaleny a Nanebevstoupení Páně i německých sekvencí jako Christ ist erstanden. Zde se s největší pravděpodobností podvoluje převládající provozovací praxi té doby. Užívání latinských sekvencí je zdokumentováno v pramenech tak raných, jako je například Naumburský církevní pořádek z let 1537/38, který předepisuje zařazení latiny a latinských sekvencí. Tendenci zachovávat čím dál tím vyšší počet sekvencí lze vypozorovat i v Psalmodii Lucase Lossia, kde počet zapsaných sekvencí s každým novým vydáním stoupá. Není bez zajímavosti, že se Chytraeus zasazuje o trvalé provozování latinských písní s cílem nedopustit, aby upadly v zapomnění. Paměť a hudba jsou zde propojeny a provozování hudby získává z hlediska uchovávání minulosti status srovnatelný s historií. Uchování vzpomínek na starou latinskou hudbu, kterou označuje za vynikající a krásnou, je zajištěno pouze tím, že se bude opakovaně provozovat. Zde je historické uvědomění opět jasně patrné.

Jakou roli hraje historie? Pohled na Chytraeovo pojetí dějin

Abychom porozuměli Chytraeovu pojetí dějin hudby a liturgie, jak je předkládá ve své agendě, je důležité podívat se na koncepty, kterými se zabývá ve svém historickém výzkumu. Jak píše ve svém spisu De lectione historiarum recte instituenda (1563), historie podává důkazy o boží moudrosti skrz biblický příběh i další důležité a památné události a osobnosti. Působí jako vitae magistra podle ciceronského konceptu, kde historie zahrnuje aspekt ponaučení. Podle Chytraea tak historiografická díla zaručují, že významné církevní, říšské a politické události neupadnou v zapomnění. Podle Chytraea minulost tudíž funguje jako návod pro budoucnost a historiografie má za cíl udržet vzpomínky na tuto minulost živé.

Role, jakou minulost hraje, a jeho vlastní chápání historie jsou v Chytraeově agendě zásadními tématy. Jeho předmluva, po velebení Boha coby Stvořitele a Spasitele, připomíná autoritám, aby se ubezpečily, že v regionech, které spravují, učí a hlásají správnou doktrínu. Tím dává jasně najevo, že tou správnou doktrínou je ta luteránská. Toto tvrzení dále podpírá historickou argumentací typickou pro kontext luteránského legitimizačního diskursu 16. století: Bůh a pravá víra jsou podle Chytraea vyjádřeni v samotném božím slově, v raných počátcích a dobách církve a v psaní proroků a apoštolů.

Tato argumentace odpovídá luteránskému nárokování správnosti vlastní konfese právě na základě toho, že je postavena na východiscích starověké církve a na Písmu v souladu s Lutherovým principem „sola scriptura“. V luteránském teologickém a historickém diskursu 16. století se tento pohled kombinoval s takovou interpretací historie, která pojímá období mezi těmito dávnými dobami a příchodem Luthera jako dobu úpadku, v níž byla pravá víra pokroucena lidským pokolením. Dalším důležitým momentem utváření identity konfese je připomínání si historických milníků, kdy se luteránská konfese nějak spojila nebo posílila. Chytraeus se tohoto procesu budování identity skrze připomínání minulosti dotýká, když zmiňuje Augsburské vyznání coby zásadní moment pro legalizaci luteránské víry. Předmluva k jeho agendě tak reaguje na tyto důležité prvky luteránského vnímání historie. Interpretace historie a její legitimizující rozměr jsou zásadní pro pochopení Chytraeova pojetí hudby a její minulosti, jelikož fungují coby intelektuální pozadí jeho koncepce hudebních dějin.

Závěr

Role minulosti v hudbě i liturgii je zásadní nejen v Chytraeově myšlení, ale i pro luteránskou konfesi celkově. Chytraeovo dílo jen rozšiřuje legitimizující luteránské historické chápání hudby. Zatímco reformační proces je legitimizován představou ideální minulosti, jejíž úpadek ukončil Luther, hudba v kostele a luteránský repertoár jsou legitimizovány jako návrat ideální podobě biblické hudby a hudby starověké církve. Skutečnost, že Lutherova hudba je pokládána za starou, jen dále podtrhuje rozlišování mezi současností, minulostí, a ještě vzdálenější minulostí biblických dob. Silná vazba na tradici a minulost je zapotřebí coby legitimizující prvek nové konfese a návod pro její budoucnost. Tyto tradiční prvky společně s Lutherovými vlastními hymny a soudobým repertoárem vytvořily hudební repertoár považovaný za skutečně luteránský a pravý. Vytváří se tak doplněk nápomocný korekci našeho chápání „konzervativních“ tendencí, které lze nalézt v polyfonii a kterým byla věnována značná pozornost badatelů; hlubší analýza Chytraea ukazuje, že se nachází i v hudbě jednohlasé. Liturgická a hudební minulost se tak stávají zásadními prvky ve vytváření jak luteránské identity, tak kolektivní hudební paměti.

Přeložila Barbora Vacková

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]Tento seriál vzniká v rámci evropského projektu HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe, který řeší mezinárodní tým muzikologů pod vedením Prof. Karla Kügleho (Utrecht) v pěti akademických institucích (Univerzita Utrecht, Univerzita Cambridge, Univerzita Curych, Univerzita Karlova Praha, Polská akademie věd Varšava).

Christine Roth studovala muzikologii a francouzskou filologii na univerzitě v Heidelbergu, byla stipendistkou King’s College v Londýně. Je doktorandkou na Univerzitě v Curychu a věnuje se luteránské hudební kultuře 16. století.

Více informací (včetně audio- a videozáznamů) najdete na webových stránkách projektu Sound Memories.[/block]

Vážení čtenáři, vzhledem k mezinárodnímu složení badatelského týmu mimořádně uveřejňujeme českou i anglickou variantu textu.

Memory and Tradition within the European Music Culture of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times

The Reformation in 16th century Germany was the origin of Lutheranism as a new Christian confession. As the reformer Martin Luther very much supported music in church, music was a major subject of discussion amongst Lutheran erudite. Luther believed music to be the highest of the arts, which was so important, that it had the second place right after theology. Music was seen by the Lutherans as a gift of God which had the power to affect the human soul and thereby to increase and strengthen the belief. It was believed to be a means to spread the Lutheran belief.

David Chytraeus and the Presence of the Past in Lutheran Music and Liturgy

Music after the Reformation thought, was not completely different from pre-Reformation music, nor had it any confessional distinction. Nevertheless, music and the conception of its past hold a special significance in defining a Lutheran cultural identity. Church orders or agendas, which are a special kind of books regulating the liturgy and music, offer insights into the Lutheran understanding of music history and their use of the historical argument in order to justify the presence of music in the church. Based on such legitimising arguments, music in the Lutheran churches in contrast to catholic church music was claimed to be a righteous practise in line with the Bible.

David Chytraeus’ agenda of 1578 is such a book regulating the liturgy and the music. Chytraeus’ agenda offers valuable insights into the Lutheran understanding of music history, its role in the denomination’s self-perception and identity, and of the role of the past in Lutheran music and liturgy as it reaches an unusually high level of detail. In the prefaces to this agenda as well as its various sections, Chytraeus provides a justification of Lutheran music and thoughts on music history. Chytraeus’ interpretation of music and its past displays significant parallels with his understanding of the historical past, especially in its alignment of theological argument and humanist historiography.

David Chytraeus and his agenda of 1578 – The historical context

David Chytraeus was a Lutheran theologian and historian. His first foray into music history was his commentary on the books of Moses In Deuteronomium Mosis Enarratio of 1575, in which he proposed a historiographic perspective that was new at the time. His interest in the musical past is also reflected in his 1578 agenda. This agenda was published as an appendix to the German translation of his catechism. Chytraeus’ catechism, first published in Latin in 1554, was one of the widely-distributed catechetic educational books of his time. It gave an introduction to the Christian doctrine for advanced students who had already studied Luther’s catechism.

The publication of Chytraeus’ agenda as an appendix to his catechism came about owing to historical circumstances related to his reformatory mission in the Archduchy of Austria. In 1568, Emperor Maximilian II had accorded freedom of religion to the Austrian Lutheran community. Chytraeus was invited the very same year to provide a church order, an order for the superintendence and the consistory, an explanation of the Confessio Augustana (doctrinale) and an order for the ordination of pastors. These documents were meant to regulate the activities of the Lutheran church in the Archduchy of Austria. However, they were never published in their entirety in Austria. The complete set of texts was issued for the first time only in 1578 in Rostock, and now encompassed the Heubstuck christlicher Lehr (the extended translation of his Latin catechism referenced above), an agenda which was based on the Austrian version of 1571, the aforementioned orders, and a liturgical calendar.

Music and liturgy in the agenda of 1578 – tradition and the musical past

The preface to the agenda already contains important information concerning Chytraeus’ views on liturgical music and its past. Singing, according to Chytraeus, is part of those rules and ceremonies not explicitly ordained by God but rather instituted by humans in order to make doctrine more understandable and strengthen belief. Therefore, singing was considered one of the so-called ‘middle things’ (adiaphora), which could be handled according to different circumstances. Chytraeus accepts adiaphora (including church music) on the condition that they are in line with the Bible, especially in cases where the scripture does not give detailed specifications. Music, even as one of the adiaphora, is thus legitimised as righteous practice. Chytraeus did not wish to homogenize liturgical practices in all Lutheran churches. On the contrary, he advocates the practice of maintaining local traditions that are in line with the word of the Bible, following the recommendations of the articles of the Augsburg confession.

Chytraeus describes in his orders for singing the use of monophonic music in the different services. Chytraeus legitimises liturgical music by enumerating passages in the bible that describe singing as a form of praising God. Typical for Lutheran thinking especially after Melanchthon, music is regarded as a gift from God given to mankind as a means of theological instruction in order to convey important articles of faith and fix them in one’s memory. The text transported through the music thus is a crucial element in the legitimisation of ecclesiastical singing, which is meant to facilitate understanding of the word of God. Chytraeus next turns to biblical texts frequently set to music as described in the Bible as types of songs. He cites the Sanctus, mentioned in the book of Isaiah, the Gloria from Luke’s gospel, the song Groß und wunderbar sind deine Werke from Revelation, and the Old Testament songs of Moses, Deborah, Barak, Hannah, Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jonas, Abacus, and especially the Psalms of David. From the New Testament he mentions the Marian Magnificat, Zechariah’s Benedictus, and Simeon’s Nunc dimittis. These examples run parallel to the general Lutheran historical argument mentioned above. Music in the church is legitimised because it is documented in the Bible, at least in textual form. Any other forms of music are left out, thereby concentrating on the theological argument of all music originating in God.

Another parallel with Lutheran historical interpretation of the biblical time—and the ancient Church as an ideal period which later declined due to human influence until Luther’s reform—is Chytraeus’ positive assessment of the bishops of the ancient Church as composers of religious music. He mentions Ambrose, Fortunatus and Prudentius. Consequently, Luther and the Bohemian Brethren, whose repertoire was partly adopted into the repertoire of Lutheran hymns and admired by Luther, are referred to as contemporary composers of music that equals the ideal music represented in the Bible and the ancient Church. Luther’s stance towards music thus is similar to his attitude towards church history, that is, a process of redemption after a long period of decline. In this respect Chytraeus’ short account on music shows traits of typical historical arguments of its time.

The musical past here is not an historical one in the modern sense. On the contrary, the historical argument here is not developed for the sake of a historiographic account but rather for the theological legitimation of music and the ideas represented by the Lutheran confession. The importance of historical arguments in this context can be found in the humanist ideals of the time. Chytraeus’ preface demonstrates his awareness of the past and of the history of music, despite the inherent limitations of the preface as a genre, which by its very nature does not allow room for more expansive elaborations.

The important role the past plays for music and liturgy can also be seen in Chytraeus’ order of the German mass included in the agenda discussed here. This order shows several particularly ‘conservative’ characteristics, compared with the well-known order of the mass by Luther.

Table 1: A comparison of the Mass Ordinary according to the Roman rite, Luther’s German Mass, and the “Agenda” of David Chytraeus

Unlike Luther in his German Mass (1526), Chytraeus begins the mass with the Veni sancte spiritus sung in German or Latin. This is a practice often found in Protestant formularies. The Kyrie, which according to Chytraeus should be in German, can be sung polyphonically. Chytraeus explicitly permits the troped Kyrie, while Luther prescribes the threefold Kyrie in the German Mass. Such troped Kyries – this is Kyries with a textual or musical extension – document the continuation of pre-Reformation and local practices. The Alleluia and the sequences for feast days are retained in Chytraeus’ agenda even though they are no longer part of Luther’s German Mass. Chytraeus’ German mass also retains the Gloria, the Gradual, the Preface, the Latin Pater noster and the German Pax Domini which originate from the Roman mass.

While offering most elements of the mass in German and omitting the elements of the Roman mass that do not theologically conform to the Lutheran understanding of the mass, Chytraeus’ mass formulary has clear affinity to the Roman model. The close relationship to the pre-Reformation mass is not unique to Chytraeus’ agenda but rather reflects the Lutheran liturgical and musical practices and the importance of local customs and their continuation.

Chytraeus also provides rules for the music of the mass proper. For the time from Christmas until Purification he calls for German Lutheran hymns, Latin carols, and German psalm songs. Interestingly, he explicitly calls Luther’s hymns “alte Geseng,” or “old songs”, stating that the old repertoire of songs is to be preferred to any newer German hymns or adaptations of Luther’s songs. Chytraeus thus perceives repertoire from the first half of the 16th century as ‘old’ and privileges this older music over contemporary repertoire.

For the following Sundays of the church year, Chytraeus lists German hymns or psalm-songs, the German Magnificat and Benedictus. It is remarkable that most of these hymns and songs are either written by Luther or originate in early Reformation songbooks such as the Achtliederbuch and the Erfurt Enchiridion. The same applies to the music Chytraeus prescribes for the period from Easter to Ascension, with the addition of the German Credo and litany. For Trinity Sunday and the following Sundays until Christmas, he also includes German versions of Ambrosian and Athanasian songs as well as one single Latin song for the twenty-third Sunday after Trinity Sunday.

Chytraeus’ agenda lists mainly German hymns for the Lutheran services throughout the liturgical year. The choice of language made in to the idea that especially non-educated people should be able to understand the songs, as Chytraeus also specifies in the preface. Latin repertoire is nevertheless present, as is typical in Lutheran contexts. For the Latin repertoire Chytraeus refers back to Lucas Lossius’ Psalmodia which was first published in 1553. The Psalmodia was a widely used Lutheran cantionale, containing all the Latin liturgical music required during the church year.

Along with others Chytraeus recommends the Latin sequences. Although Luther had limited the number of sequences to three (Sancti spiritus assit nobis gratia, Veni sancte spiritus, Grates nunc omnes), Chytraeus lists many more including Latin sequences for Easter, Pentecost, Trinity, the feast of Mary Magdalene, and Ascension as well as German sequences such as Christ ist erstanden. Here he most likely defers to the predominant musical practice of the time. The use of Latin sequences is documented in sources as early as in the Naumburg church order of 1537/38, which prescribes the inclusion of Latin language and of Latin sequences. The retention of a growing number of sequences can also be seen in Lucas Lossius’ Psalmodia where the number of sequences was augmented in every new edition. Interestingly, Chytraeus advocates the continued use of the Latin songs in order to prevent them from being forgotten. Memory and music are linked here, and the practice of music gains a status comparable to history in conserving the past. The retained memory of the old Latin music, which he characterises as beautiful and splendid, is ensured only through its ongoing use. Here again, a consciousness of a musical past is clearly apparent.

What is the role of history? – a look into Chytraeus’ ideas on history

In order to understand Chytraeus’ notion of the past in music and liturgy as put forth in his 1578 agenda, it is important to consider the concepts of history he engages with in his historical research. As Chytraeus writes in his De lectione historiarum recte instituenda (1563), history evidences the divine wisdom through the example of the biblical story itself, as well as other important and memorable events and personalities. History thus acts as vitae magistra – a Ciceronian concept of the instructive dimension of history. According to Chytraeus, historiographical works also ensure that major ecclesiastical, imperial and political events are not forgotten. For Chytraeus the past thus serves to guide the future, and historiography has as its goal keeping the memory of the past alive.

The role of the past and Chytraeus’ understanding of history are also important elements in the preface to his 1578 agenda. Chytraeus’ preface begins, after praising God as creator and redeemer, by reminding the authorities to ensure that the true doctrine is taught and publicly professed the regions they govern. He thereby asserts implicitly that the Lutheran confession is the true doctrine. He continues to authorise this implicit assertion with an historical argument typically found in the context of sixteenth-century discourse of Lutheran legitimation: God and the true religion are displayed, according to Chytraeus, in God’s own word, in the earliest beginnings of the church and in early days of the church and in the writings of the prophets and apostles.

This argument corresponds to the Lutheran claim of confessional correctness by having recourse to the ancient church and the word of scripture, following Luther’s principle of sola scriptura. In Lutheran theological and historical discourse of the sixteenth century, this viewpoint was combined with an interpretation of history that construes the time between these early years and Luther’s appearance as a period of decline, during which the true faith was distorted by mankind. Furthermore, the commemoration of milestones uniting or fortifying the Lutheran confession gains even greater importance for the construction of a confessional identity. Chytraeus refers to this identity-building practice of commemoration when mentioning the Augsburg Confession as a crucial moment in the legalisation of the Lutheran faith. The preface to the 1578 agenda is thus in dialogue with these important elements of Lutheran historical sensibility. This historical interpretation and its legitimising scope are crucial to understand of Chytraeus’ notion of music and its past, since it stands as the intellectual background of his concept of music history.

Conclusion

The role of the past in music and liturgy is crucial not only in Chytraeus’ thinking but also for the Lutheran confession. Chytraeus’ work broadens the legitimising Lutheran historical understanding of music. While the reforming process is legitimised by the idea of the decline of an ideal past, brought to an end by Luther, music in the church and the Lutheran repertoire more specifically is legitimised as a return to the ideal state of biblical music and the music of the ancient church. The fact that Luther’s music is already considered old underscores a differentiation between the contemporaneous, the old, and the even more distant past of biblical times. The strong bond to tradition and to the past is needed as a legitimising element of the new confession and as guidance for its future. These traditional elements, together with Luther’s own hymns and contemporaneous repertoire build a musical repertoire considered genuinely Lutheran and true. This constitutes a helpful corrective supplement to our understanding of ‘conservative’ tendencies, which are so clearly to be found in polyphony, and have received more attention in scholarship: a closer analysis of Chytraeus demonstrates that they are clearly to be found in monophonic music too. The liturgical and musical past thus become essential elements in the construction of both a Lutheran identity and a shared musical memory of the past.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]This series has been published as part of the European project HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, undertaken by an international team of musicologists led by Prof. Karl Kügle (Utrecht) in five academic institutions (Utrecht University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Zurich, the Charles University in Prague, and the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw).

Christine Roth is a doctoral student at the University of Zurich. Under the supervision of Professor Inga Mai Groote, she studies the musical culture of the Lutheran church in the sixteenth century.

More information (including audio and video recordings) see on Sound Memories project website.[/block]

This project has received funding from the H2020-EU.3.6 – SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307. The project Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe is financially supported by the HERA Joint Research Programme (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, PT-DLR, CAS, CNR, DASTI, ETAG, FCT, FNR, F.R.S.-FNRS, FWF, FWO, HAZU, IRC, LMT, MIZS, MINECO, NCN, NOW, RANNÍS, RCN, SNF, VIAA, VR and The European Community, SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307.

|

|

|