[block background=“#e5e5e5″]For English version of the article please see below.[/block]

Hudba na středoevropských univerzitách 14. a 15. století

Studentská středověká tvorba, zejména Závišova píseň, Otep myrhy a Andělíku rozkochaný mají své neotřesitelné místo v osnovách výuky literatury na středních školách. Méně zmiňovanou skutečností však je, že život na středověké univerzitě měl více vrstev. Byl velmi organizovaný a hudba zněla v univerzitním životě daleko častěji než Gaudeamus igitur, které slýchávají dnešní studenti při imatrikulacích a promocích.

Hned pro několik členů projektu Sound Memories, který si v této sérii představujeme, je pozdně středověká univerzita objektem zájmu a klíčovou institucí, kde vznikalo množství pozoruhodné hudby. O univerzitách se v literatuře často prohlašuje, že jsou tavícím kotlíkem neboli tyglíkem různorodých myšlenek. Jak se ale faktor kotlíku projevoval v hudební praxi?

Musica jako součást sedmera svobodných umění

Pokud se ve středověkých studijních plánech objevila musica, nebyla to hudební výchova, jak bychom si dnes nejspíš představovali. Byla to spíše filozofická disciplína, která spočívala v četbě Boethiova spisu De institutione musica a studiu antické a středověké hudební teorie.

V pozoruhodném kontrastu stojí tradiční prestiž této teoretické podoby hudebních studií se společenskou prestiží reálně znějící hudby a jejích provozovatelů. Teorie hudby byla již od dob karolínské renesance součástí středověkého vzdělávacího systému. V rámci sedmera svobodných umění patřila ke čtyřem vyšším disciplínám. Znějící hudba však měla pozici složitější. Je známo, že hudba ve formě jednohlasého latinského liturgického zpěvu byla hlavním médiem Boží chvály. Církevní autority si však uvědomovaly, že hudba má stejně tak silnou schopnost stát se v mžiku nástrojem ďáblovým a svádět k hříchu. Vícehlasá hudba, hudební nástroje a zejména taneční hudba se pravidelně stávaly předmětem zákazů a regulací. Často se jednalo o oblíbené žánry hudební zábavy, které se různými skulinkami prodíraly do sféry bohoslužebné hudby.

Ovšem i k zdánlivě nejváženější formě znějící hudby – liturgickému zpěvu – se společnost chovala poměrně macešsky. Krásně to ilustruje následující příklad. Listujeme-li středověkými knihovními katalogy, můžeme narazit na situaci, kdy jsou všechny traktáty a literární díla v nějakém konkrétním rukopise pečlivě vypsány včetně autorů. A nakonec se často objeví poznámka „item quedam musica“ – „také nějaká hudba“. Toto zdánlivě druhořadé postavení znějící hudby ve vztahu k jiným disciplínám lidské činnosti můžeme pozorovat i v detailech naší současnosti. Např. v závěrečných titulcích filmů jsou hudebníci a použité skladby uvedeny až těsně v závěru. Analogických příkladů by se ale našlo více. Ani dnes nepožívají hudebníci ve společnosti takové vážnosti jako např. právníci a lékaři, pokud se jim tedy nepodařilo dosáhnout výrazného uznání překračujícího hranice oboru. Ale zpět k historickým pramenům. Zvláštní ironií osudu jsou pro nás muzikology právě tyto stránky s „nějakou hudbou“ těmi nejdůležitějšími, protože často jsou na nich zapsány jedinečné kompozice v originálních kontextech. Společná výpověď zapsané hudby, původu rukopisu a osobnosti písaře nebo prvního majitele rukopisu je základem bádání o této hudební kultuře.

Hudba jako individuální zájem studentů

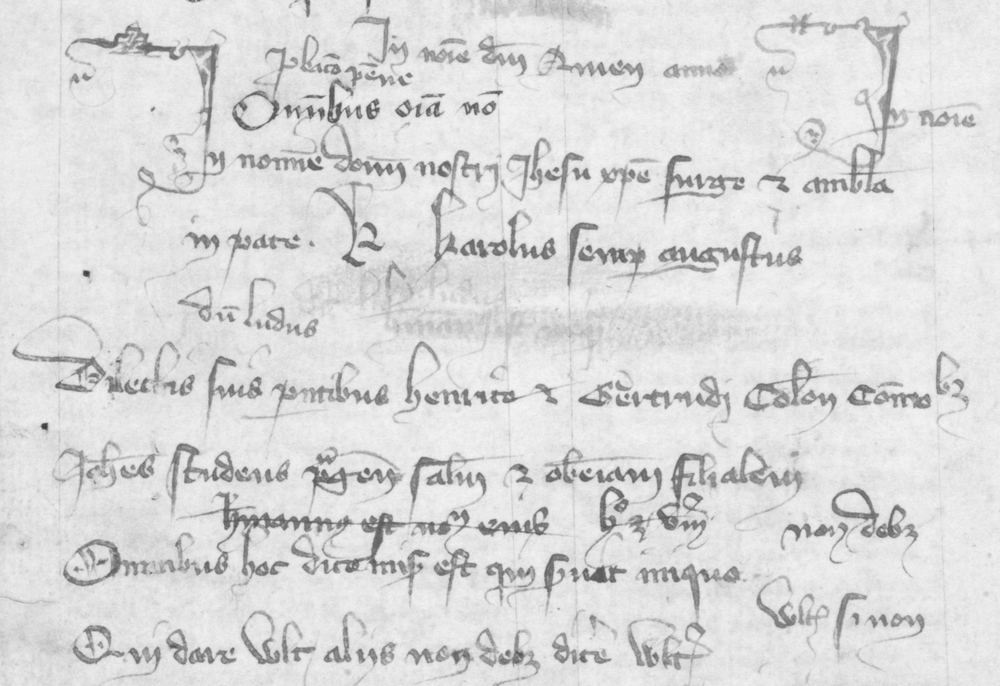

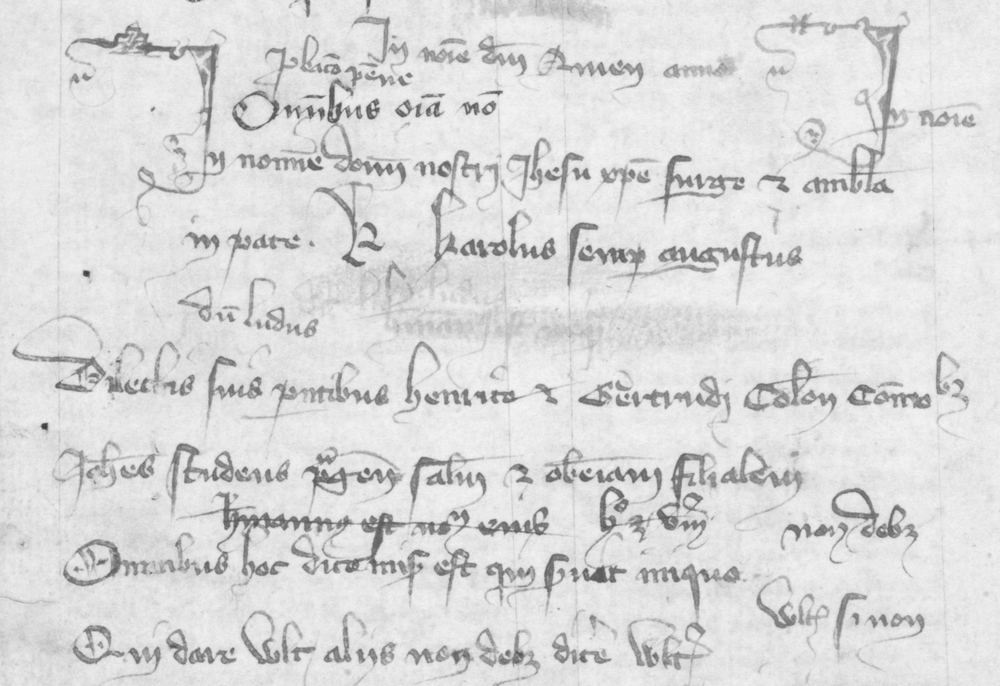

Studenti si občas doslova naškrábali text nějaké písně na volné místo rukopisů s kázáními nebo traktáty. Simon Batz von Homburg, doktor práv z Erfurtu a později vysoce postavený úředník hanzovního města Lübecku v 15. století, sbíral nejrůznější texty. Duchovní písně, ale i sprosté a rouhavé básně, které za svého života pečlivě střežil v osobním sborníku. Latina byla pro studenty jazykem, kterému mimo jejich komunitu málokdo rozuměl tak, aby odhalil zapisování nepřístojností. Přesto písaři někdy sáhli k řečtině jako k dokonalejší šifře pro skrytí nejpeprnějších výrazů. Simon Batz svůj zápisník z univerzitních let za života patrně nedal z ruky, ale po jeho smrti se tato sbírka ocitla ve fondu městské knihovny v Lübecku a patří k nejvýznamnějším kolekcím svého druhu.

V jiném rukopisu, který Batz odkázal též městu Lübeck, je na konci teologického traktátu o umírání připsán text písně Audi tellus, která se zpívala jako tropus, neboli doplněk k responsoriu Libera me, Domine. Píseň začíná působivým zvoláním: „Slyš, Země, slyš, velké moře kolem ní, slyš všechno, co žije pod Sluncem, jak je krása a sláva tohoto světa falešná a pomíjivá!“. Důkazem pomíjivosti je pak impozantní defilé starozákonních a antických postav, jež ani jejich výjimečné zásluhy neochránily před osudem všech smrtelníků. Na konci písně se text obrací k Bohu jako vládci nad temnotou, čímž je atmosféra obecného zmaru opět projasněna.

V jiném rukopisu, který Batz odkázal též městu Lübeck, je na konci teologického traktátu o umírání připsán text písně Audi tellus, která se zpívala jako tropus, neboli doplněk k responsoriu Libera me, Domine. Píseň začíná působivým zvoláním: „Slyš, Země, slyš, velké moře kolem ní, slyš všechno, co žije pod Sluncem, jak je krása a sláva tohoto světa falešná a pomíjivá!“. Důkazem pomíjivosti je pak impozantní defilé starozákonních a antických postav, jež ani jejich výjimečné zásluhy neochránily před osudem všech smrtelníků. Na konci písně se text obrací k Bohu jako vládci nad temnotou, čímž je atmosféra obecného zmaru opět projasněna.

Seznam postav v písni Audi tellus patří k těm rozměrnějším, ale drobné „náhrobní kameny“ skupin starozákonních aktérů lze v písňových textech najít často. David, Šalamoun a Absolon se spolu objevují pravidelně. Další takovou skupinkou jsou Ester, Támar a Rebeka, ženy figurující v knize Ester. Studenti vždy tíhli k zapisování neotřelého materiálu. Kromě čistě estetických pohnutek takové texty pomáhaly udržet biblické reálie v hlavách zapomnětlivých žáků.

I v pražských sbírkách se dochoval rukopis s kolekcí netradičních mariánských textů. Že rukopis pochází z prostředí pražské univerzity, je zřejmé z přípisu, kdy si jistý Johannes studens Pragensis zkoušel, jak napsat latinské pozdravení pro své rodiče, kteří dlí v Kolíně (patrně ten nad Rýnem). V tomtéž rukopise je zapsána i známá píseň O quantum sollicitor, která svou kritičností vůči kléru jako by vypadla ze sbírky Carmina Burana.

Otázkou, která dodnes zaměstnává muzikology i liturgiky je, zda tyto nové duchovní písně mohly zaznívat při liturgii v kolejních kaplích. Již od druhé poloviny 15. století tomu tak u uměřenějších a zbožnějších textů bezpochyby bylo, ale ve 14. století se ještě mohlo jednat o neoficiální a spíše tiše trpěnou praxi omezenou na několik málo progresivních institucí. Tomu nasvědčuje nejstarší podoba dochovaných písní. Ty byly vytvářeny za pomoci staré a osvědčené techniky tropování. Jen tak byla přítomnost nově komponovaných písní v liturgické hudbě akceptovatelná. Stará a tradiční kompoziční technika tak v počátcích pomohla legitimizovat jednu z největších změn v západní liturgické hudbě, a tou bylo postupné nahrazování chorálního mešního propria nově komponovanou hudbou.

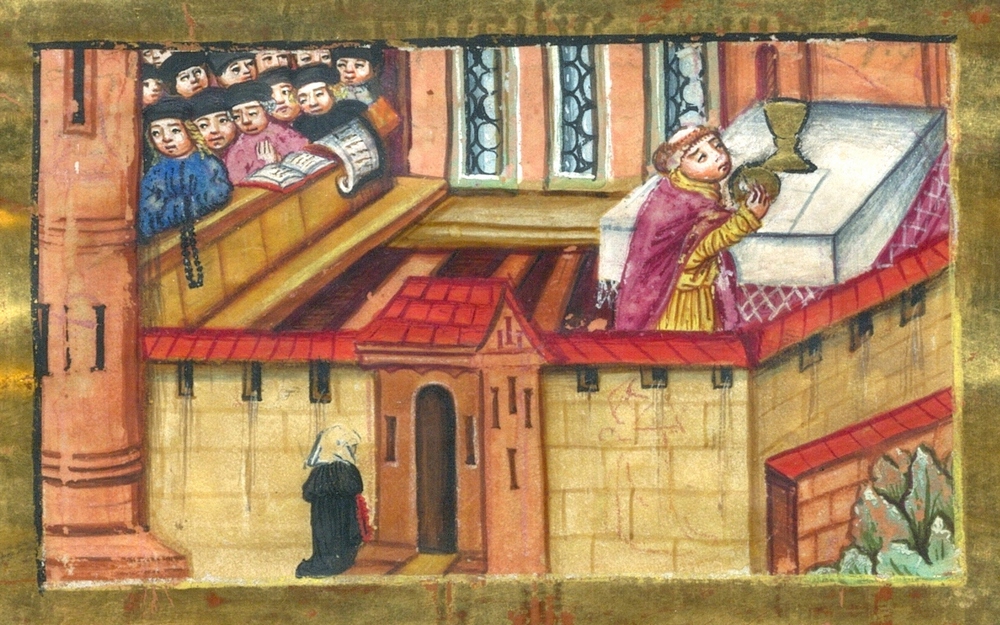

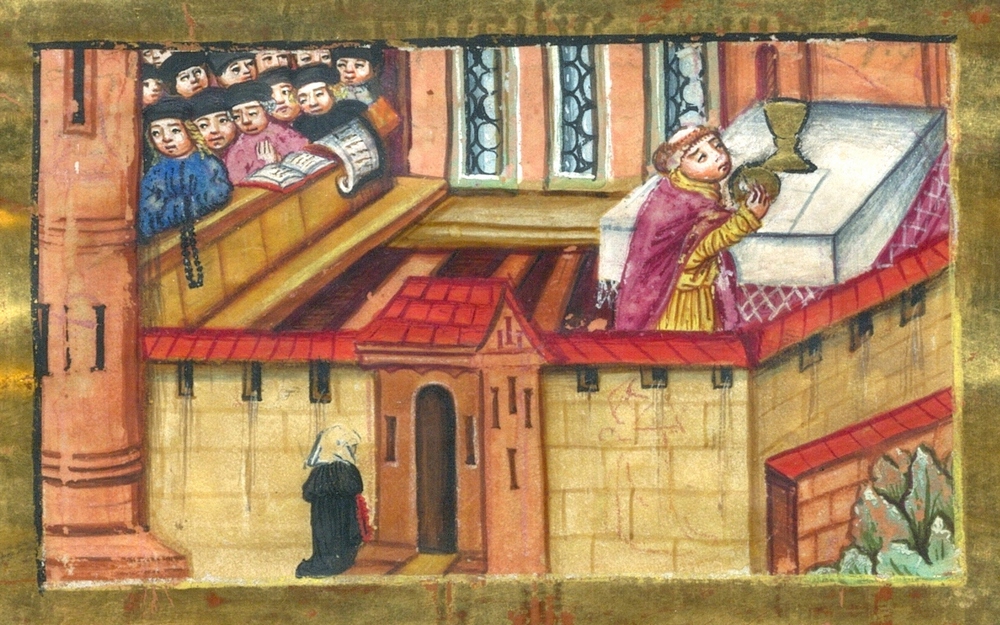

Officium v kolejních kaplích

Dnes málo známou, ale ve středověku neodmyslitelnou součástí hudebního života univerzity byla hudba při bohoslužbách. Není to ani velká nadsázka, řekneme-li, že se středověký žák svým vzděláním „prozpíval“ až k diplomu. Komunita studentů se ve své organizaci života podobala řeholnímu konventu, protože musela dodržovat statuta, v nichž byl pevně stanoven rozvrh mší a modliteb hodinkového officia. Studenti byli povinni absolvovat průměrně jednu mši denně a většinu dní v roce i ranní chvály a nešpory.

V Praze, konkrétně v Rečkově koleji se dochoval unikátní soubor nehudebních pramenů, které umožňují rekonstruovat studentskou liturgii po celý církevní rok. Kolej založil staroměstský purkmistr Jan z Ledče, řečený Reček. Byla to první kolej založená po utichnutí husitských nepokojů a její fundaci motivovala snaha pozvednout skomírající renomé pražské univerzity. Statuta koleje, která nechal sepsat sám zakladatel, odhalují, jaké slavnosti a svátky studenti slavili a koho ze světců si připomínali. Podrobný katalog kolejní knihovny a seznam knih v kolejním kostele pak umožňují rekonstruovat hudební repertoár, kterým byl tento rozvrh naplněn.

Nepřekvapí, že ze světců byla pozornost věnována českým patronům sv. Václavovi, Vojtěchovi, Prokopovi a Ludmile. V liturgii se objevují i světice jako sv. Kateřina, Barbora a Dorota, které byly ve větší míře uctívány od doby Karla IV. Studenti dokonce byli povinni ctít i další předhusitskou tradici, sobotní ranní mše k poctě Panny Marie, tzv. matury. Za zmínku stojí pondělní bohoslužby, kdy si kolejní osazenstvo připomínalo zesnulé členy akademické obce a dobrodince, kteří kolej podporovali finančně a materiálně. V případě Rečkovy koleje byly zádušní mše věnovány zakladateli koleje Janu z Ledče a dále pak císaři Zikmundovi.

Jakkoli se nám dnes objem studentské liturgie může zdát úctyhodný, ve srovnání s nabitým rozvrhem, který absolvovali středověcí mniši a kanovníci, se jedná pouze o zlomek povinností. Však již od doby Karla IV. a Arnošta z Pardubic byla snaha, aby se studenti více věnovali studiu a nemuseli trávit celé dni v kostele. Přísný režim bohoslužeb, který je zachycen v Řeholi sv. Benedikta, dnes zachovávají jen nejstriktnější mnišské komunity, např. trapisté a trapistky. Na druhou stranu, ještě na konci 90. let 20. století zažil autor těchto řádků liturgii podobnou té pražské z 15. století v katolickém internátu pro středoškoláky v bavorském Pasově.

Mezi večeří a modlitbou

Z hlediska tvořivosti v kolejních budovách se zdá být klíčovým neformální čas, který studenti společně trávili mezi večeří a posledními modlitbami dne. Na počátku 15. století je na vídeňské univerzitě, která se v mnohých aspektech podobala té pražské, doložena praxe, kdy se studenti teologie v malých skupinkách po večerech cvičili v kazatelském umění. Formou samostudia se tak připravovali na svou budoucí dráhu mimo univerzitní půdu.

Podle podoby dochovaných hudebních pramenů z univerzitního prostředí ale můžeme náplň těchto sezení směle rozšířit i o prohlubování praktických hudebních dovedností, které se oficiálně nevyučovaly. V rukopisech nacházíme stránky popsané notovanými písněmi, chorálními zpěvy, texty sekvencí, ale i pokusy o vícehlasou kompozici. K nalezení jsou i vypsané jednoduché nápěvy mešních prefací. To jsou sice zpěvy založené na nejjednodušších recitačních formulích, ale kněží je museli zvládnout zazpívat sami, tedy i ti méně hudebně zdatní. Pomocí zapsané melodie si je mohli osvojit spolehlivěji.

I na studenty, kteří se nevydali na striktně duchovní dráhu, čekala nutnost ovládat chorální zpěvy. Každý středověký student si s sebou sice přinesl z dětského věku zkušenost se zpěvem na kůru. Ovšem zvládnout zpěvy tak, aby je mohli provozovat v roli duchovních a předávat zkušenosti dále, vyžadovalo určité nasazení a nezbytnou přípravu.

Ušlechtilá zábava nebo existenční nutnost?

V pojednáních univerzitní hudby a latinské písňové tvorby středověku si autoři kladou otázku, kde a v jakém společenském kontextu tato hudba zněla. Často je skloňována ušlechtilá zábava kléru. V případě absolventů středoevropských univerzit by se ale mohlo jednat i o něco jiného. V 15. století vzrůstala obliba tzv. votivních bohoslužeb. Bohatí měšťané vynakládali nemalé částky na provozování liturgie za duše svých předků a též si „předpláceli“ bohoslužby za své duše. V kostelích byly zakládány oltáře a votivní kaple, kde tyto bohoslužby probíhaly. Schopnost tvořit a provozovat krásnější, zbožnější a bohatší hudbu poskytovala duchovním a čerstvým absolventům studií i jakousi konkurenční výhodu. Mohla se stát cestou k většímu množství „zakázek“, tedy i zlepšení jejich vlastní ekonomické situace. I absolventi lékařských a právnických studií často začínali svou kariéru ve funkci ředitelů kůru, než se jim podařilo získat prestižnější posty. Je nasnadě, že ne všichni vykonávali toto nutné „zlo“ s láskou.

V důsledku toho, že se do kompozice nových písní pouštěli i ti méně nadaní, sledujeme v rukopisech různou kvalitu zápisů melodií i textů. Od těch geniálních až po prosté skládačky z již existujících zpěvů. Určitý tlak na produkci poutavé duchovní hudby se mohl projevovat v kompozici textů, které překypovaly množstvím zdrobnělin, nečekaných metafor i humorných nadsázek. S touto hudební tvořivostí však v 16. století rázně zatočila doba reformace a Tridentský koncil, ale to už by byl námět na jiný text.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]Tento seriál vzniká v rámci evropského projektu HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe, který řeší mezinárodní tým muzikologů pod vedením Prof. Karla Kügleho (Utrecht) v pěti akademických institucích (Univerzita Utrecht, Univerzita Cambridge, Univerzita Curych, Univerzita Karlova Praha, Polská akademie věd Varšava).

Jan Ciglbauer studoval hudební vědu na Univerzitě Karlově v Praze a Freie Universität v Berlíně. V roce 2017 zakončil doktorské studium pod vedením Davida Ebena prací Cantiones Bohemicae – Komposition und Tradition. Zabývá se výzkumem a edicí středoevropských latinských písní. Studuje proměny jejich formy i společenské funkce v průběhu 14. a 15. století a jejich roli v oficiálním i neoficiálním životě univerzitních vzdělanců.

Více informací (včetně audio- a videozáznamů) najdete na webových stránkách projektu Sound Memories.[/block]

Vážení čtenáři, vzhledem k mezinárodnímu složení badatelského týmu mimořádně uveřejňujeme českou i anglickou variantu textu.

Memory and Tradition within the European Music Culture of the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times

The first association that comes to many people’s minds when they hear the words music, university, and the Middle Ages are the poetic side products of the unbound creativity of the young people of the time, brought together in the ecosystem of a medieval university by a common desire for education and better living. Thanks to several publications in the past decades, we can get a taste of these frolicsome and often bitingly ironic poems. In the Czech milieu, they were most extensively presented in the anthology Carmina Scholarium Vagorum (“Songs of Rogue Pupils”) put together by Rudolf Mertlík and Anežka Vidmanová as well as an older study by Jan Vilikovský from the first half of the 20th century.

Resounding Universities at the End of the Middle Ages

The medieval student songs, especially Záviš’s song, The Bundle of Myrrh and Angelic Messenger of Love, have found a stable place in the literature curriculum of traditional secondary schools. Yet it is scarcely pointed out that life at a medieval university had many more layers to it. University life was highly organised and music was part of it to a much greater extent than we imagine, being familiar with little more than the Gaudeamus igitur that today’s students hear at matriculation and graduation ceremonies.

The late-medieval university as a milieu featuring plenty of remarkable music has become a key object of interest to several members of the Sound Memories project. Field literature often refers to universities as melting pots of diverse schools of thought. In what ways does this statement apply to musical praxis?

Musica as one of the seven liberal arts

If a curriculum at a medieval university contained musica, it did not refer to music education as we know it today but represented a rather philosophical discipline consisting of the reading of theoretical texts on music and the works by Boëthius.

The traditionally prestigious position of these theory-oriented music studies stands in remarkable contrast to the social status of actual resounding music. Music theory as part of the quadrivium occupies a prominent position in Alcuin’s classification of the seven liberal arts. Music praxis was in a more difficult position, though. It is generally known that music in the form of monophonic Latin liturgical singing was the main medium for the worship of God. However, the church authorities realized that music was also rather prone to becoming the devil’s tool, corrupting and tempting souls to sin. That is why polyphonic, instrumental, and most of all dance music balanced between the status of attractive, elitist, complex, and prestigious entertainment and something that was reluctantly permitted or sometimes even banned by authorities.

Surprisingly, even the most venerated form of resounding music, namely liturgical singing, was subject to certain mistreatment. This is well illustrated by the following example: when we page through medieval library catalogues, all treatises and literary works are listed carefully including the names of their authors. At the end, there is often a little note: item quedam musica (“and also some music”). Even nowadays we might find parallels to this seemingly second-rate position of resounding music in comparison to other disciplines of human activity. For example, musicians and compositions featured in a film are listed at the very end of the credits. Also, in middle-class society musicians do not have a social status comparable to that of lawyers or physicians (unless there has been some extraordinary achievement on their part). However, if we turn back to historical sources, we find an interesting paradox: for musicologists, precisely the pages with “some music” are the most valuable ones, because they often reveal unique compositions in their original contexts. The information that we elicit from the music itself, its origin and the identity of the scribe or the first owner of a manuscript, forms the basis for research of this musical culture.

Music as the students’ individual interest

Students often scribbled song lyrics in the margins of sermons or treatise manuscripts. Simon Batz von Homburg, a Doctor of Law from Erfurt and later a high-ranking official of the Hansa city Lübeck in the 15th century, was a collector of miscellaneous texts. His well-guarded private anthology contained sacred songs as well as vulgar or blasphemous poems. Latin was a language that enabled students to exchange improprieties without being caught, because the language was understood by few outside their community. Yet the scribes sometimes turned to Greek as an even better code for concealing the most pungent expressions. Simon Batz probably never let this university notebook out of his hands during his lifetime, but after he died, the collection was acquired by the municipal library of Lübeck and now ranks among the most valuable collections of its kind.

In another manuscript that Batz bequeathed to the city of Lübeck, there is an addition to the theological treatise on dying written at its very end, namely the lyrics to the song Audi tellus that was sung as a trope or supplement to the responsory Libera me, Domine. The song starts with the impressive exclamation: “Behold, Earth, behold, great sea that surrounds it, behold, ye all that live under the Sun, how fleeting is the beauty and glory of this world!” What follows as evidence proving this ephemerality is an overwhelming display of personae from the Old Testament and the ancient world who, despite their extraordinary achievements, did not escape meeting the fate of all mortals. At the end, the lyrics address God as the one who rules over the darkness, in this way brightening up the atmosphere of universal decline.

The list of characters in Audi tellus ranks among the more extensive ones, but little “tombstones” to Old-Testament personalities or groups of characters appear in manuscripts on a regular basis. David, Solomon, and Absalom represent one such group; another includes Esther, Tamar, and Rebecca, women from the biblical book of Esther. Students always tended to note down unusual material. Besides aesthetic reasons, it was often the need to fix biblical knowledge in the memory that made them jot down verses.

Prague collections also include a manuscript with non-traditional Marian texts. The fact that it comes from the milieu of Prague University is evidenced by the note made by a certain Johannes studens Pragensis in which he practised the writing of a Latin greeting addressed to his parents living in Cologne (probably the one on the river Rhine, Germany). The same manuscript contains the well-known song O quantum solicitor which, in its critical stance to the clergy, is evocative of Carmina Burana.

Both musicologists and liturgists keep trying to find out whether these new sacred songs might have been performed during the liturgical services in college chapels. It was undoubtedly the case with the more restrained and devout texts from the mid-15th century onwards, but in the 14th century one may rather speak of a non-official and reluctantly tolerated praxis at a few progressive institutions. This is suggested by the earliest versions of the songs that survive. These were created by means of the old and time-tested technique of adding tropes to plainchant, as this was the only way to justify the inclusion of newly composed songs into liturgical music. Thus, the traditional compositional technique helped legitimate one of the greatest changes in Western liturgical music, namely the gradual substitution of Gregorian chants by songs.

The Divine Office in college chapels

Music in liturgy represents a less known part of musical life at medieval universities. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that, in the Middle Ages, students often “sang their way” to graduation. To a certain extent, the student community resembled the convent community in the way its daily life was organized. Students had to obey statutes which prescribed a fixed schedule of daily masses and prayers within the Liturgy of the Hours (the Divine Office). They were obliged to take part in one mass a day on average as well as attend morning worship and vespers.

In Reček’s college in Prague a unique set of non-musical sources has survived that enables us to reconstruct the student liturgical practice throughout the church year. The college was founded by the Old-Town mayor Jan of Ledeč (called Reček) and was the first college to be established after the Hussite riots had calmed down. Its founding was motivated by the effort to raise the fading reputation of Prague University. The college statutes set by the founder himself reveal what feasts and holidays were celebrated by students and which patrons they worshipped. A detailed catalogue of the college library kept in the college church enables scholars to reconstruct the music repertoire within this schedule of holidays.

It comes as no surprise that the greatest share of attention was paid to Czech patron saints – St Wenceslas, St Adalbert of Prague, St Procopius, and St Ludmila. The liturgy involves female saints too, such as St Catherine, St Barbara, and St Dorothea who were worshipped from the time of the Charles IV onward. Students were even obliged to keep another pre-Hussite tradition, namely a Saturday morning mass to St Mary called matura. Among the services worth mentioning is a regular Monday mass devoted to the memory of the deceased members of the academic community as well as benefactors who supported the college both financially and materially. In Reček’s college, the requiem masses were dedicated to the founder of the college Jan of Ledeč and Emperor Zikmund.

However extensive the volume of mandatory student liturgy may seem to us nowadays, the students’ obligations represented just a fragment of the busy liturgical schedule observed by medieval monks and canons. No wonder that as of the time of Charles IV and Archbishop Arnošt z Pardubic there were efforts to reduce the liturgical duties of students in favour of more intensive study. The strict regime of services recorded in the Rule of St Benedict is nowadays adhered to only by the most stringent monastic communities such as the Trappists. However, in the late 1990s the author of this study attended a service at a Roman Catholic boarding school in Passau, Bavaria which resembled the liturgy as celebrated in 15th century Prague.

Between prayer and dinner

As far as creativity in colleges is concerned, the time that seems to be of crucial importance is the period between dinner and the last prayers of the day when the students were often gathered together. There is evidence suggesting that at the beginning of the 15th century, students of theology at the University of Vienna (which in many aspects resembled Prague University) often got together in the evenings to practise their preaching skills in little groups. In this way – by means of self-study – they prepared for their future careers outside the university grounds.

However, surviving musical sources from university milieu indicate that these sessions most likely also included the enhancement of practical music skills that were not officially taught. Manuscripts contain pages filled with notated songs and chants, texts of sequences, and even attempts at polyphonic compositions, and there are also simple tunes of mass prefaces. Although these are melodies based on the simplest reciting formulae, priests (including those with less musical talent) had to be able to sing them on their own. Noting down the melody helped them master it more efficiently.

Even students who did not set out for clerical careers were expected to master choral singing, though. Every medieval student had entered university having had the experience of singing at a church choir. However, mastering the singing to an extent where they could perform it as clergymen and pass it on to others required a certain amount of effort and preparation.

Cultured entertainment or existential necessity?

In studies dealing with university music and Latin medieval songs, scholars try to figure out where the music was performed and in what social context. Among frequent answers is the cultured entertainment of the clergy. Yet in the case of medieval university graduates there might be something else as well. In the 15th century, votive masses became rather popular – wealthy citizens paid substantial sums of money to have masses served for the souls of their ancestors, or, for that matter, for their own souls in the future. Special altars and votive chapels were established in churches where these masses were celebrated. The ability to create and produce more beautiful, pious, and magnificent music provided the clergy with a kind of competitive advantage, as more votive “orders” meant the improvement of the economic situation of the church. Even graduates of medicine and law study programmes often began their careers as choir directors before they managed to find more prestigious posts. We may assume that not all of them carried out this “necessary evil” enthusiastically.

The fact that even the less gifted tried to compose new songs is reflected in the varying quality of melodies and texts found in manuscripts, which range from brilliantly original creations to simple modifications of existing songs. Demand for new and attractive sacred music seems to be reflected in the fact that the newly composed texts feature a lot of diminutives, surprising metaphors, and humorous hyperboles. This musical creativity was, however, abruptly terminated by the period of Reformation and the Council of Trent, but that would be another study.

[block background=“#e5e5e5″]This series has been published as part of the European project HERA Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe, undertaken by an international team of musicologists led by Prof. Karl Kügle (Utrecht) in five academic institutions (Utrecht University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Zurich, the Charles University in Prague, and the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw).

Jan Ciglbauer is a researcher in the Institute of Musicology at the Charles University’s Faculty of Arts. His research is directed toward the monophonic song repertory of the late Middle Ages and the musical culture of medieval universities.

More information (including audio and video recordings) see on Sound Memories project website.[/block]

This project has received funding from the H2020-EU.3.6 – SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307. The project Sound Memories: The Musical Past in Late-Medieval and Early-Modern Europe is financially supported by the HERA Joint Research Programme (www.heranet.info) which is co-funded by AHRC, AKA, PT-DLR, CAS, CNR, DASTI, ETAG, FCT, FNR, F.R.S.-FNRS, FWF, FWO, HAZU, IRC, LMT, MIZS, MINECO, NCN, NOW, RANNÍS, RCN, SNF, VIAA, VR and The European Community, SOCIETAL CHALLENGES – Europe in a Changing World – Inclusive, Innovative and Reflective Societies under grant agreement no. 649307.

|

|

|